Apotheosis

I had waited for decades for this opportunity.

It was the turn of the millennium. I’d observed, studied, recorded, and reported on Common Loon behaviors, populations and productivities, and conservation since 1978 in New Hampshire and Maine, and now in my first years in Alaska. I had a good background and savvy of the critter, based primarily on simple observation. I’d kept it simple, and I felt comfortable with what I knew.

Plus, I had recently been hired to write about the Yellow-billed Loon (YBLO), which inhabits the far North, the ultimate tundra, my final wilderness dream, and my ultimate participation on the cutting edge of loon science and conservation. My report on the Status and Significance of Yellow-Billed Loon Populations in Alaska had just been published by The Wilderness Society and Trustees for Alaska (2002). I believed I held the credentials to tread upon the high latitude habitat and experience the presence of the wildest of loons. That was my dream.

Plus, I had recently been hired to write about the Yellow-billed Loon (YBLO), which inhabits the far North, the ultimate tundra, my final wilderness dream, and my ultimate participation on the cutting edge of loon science and conservation. My report on the Status and Significance of Yellow-Billed Loon Populations in Alaska had just been published by The Wilderness Society and Trustees for Alaska (2002). I believed I held the credentials to tread upon the high latitude habitat and experience the presence of the wildest of loons. That was my dream.

And now I was at the pivotal point—one might say the apotheosis—of what was likely the final chapter of my loon work. I was out here on the tundra at 71º North Latitude of the Western Arctic of Alaska—300 miles north of the Arctic Circle—to begin a multi-year research project into the fifth and rarest species of loons, the Yellow-billed Loon, an almost identical cousin to the Common Loon, but a nester on the Arctic tundra, not the Common Loon’s northern forest biome. I’d met USGS wildlife biologist Dr. Joel Schmutz a year before, back in Anchorage. Joel had come to a meeting of Alaskan loon biologists as a goose biologist who had collected data on the Red-throated Loons in his study area. His report on the red-throats was the best scientifically executed presentation of the meeting, by far.

I chased him down after his delivery and suggested that he might look into the future of the YBLO in Alaska, and if so, that I would volunteer to be there with him, with my own experience of the behaviors of Common Loons, with whom I supposed shared many similar behaviors. Now it was coming true. And I so wanted a taste of that tundra, the Arctic wild, and its loons who nested there.

So here we were, half a dozen of us, having flown up from Anchorage to Barrow (now Utqiagvik) by jet, and then by small Cessna seaplane back down into the YBLO’s thicker nesting area west of Teshekpuk Lake. Joel and I were a team. We had found the YBLO nest from the air and touched down on the next lake over so as not to freak out the incubating loon. We had set up a nest trap around the nest and then withdrawn, Joel staying close but hopefully out of sight from the incubating bird, and myself at least a quarter mile away on a low ridge behind some tall vegetation from which I could see the nest. We were connected by two-way radio, and Joel was connected to the nest trap with a remote trigger to spring the trap when the bird was back on the nest.

So here we were, half a dozen of us, having flown up from Anchorage to Barrow (now Utqiagvik) by jet, and then by small Cessna seaplane back down into the YBLO’s thicker nesting area west of Teshekpuk Lake. Joel and I were a team. We had found the YBLO nest from the air and touched down on the next lake over so as not to freak out the incubating loon. We had set up a nest trap around the nest and then withdrawn, Joel staying close but hopefully out of sight from the incubating bird, and myself at least a quarter mile away on a low ridge behind some tall vegetation from which I could see the nest. We were connected by two-way radio, and Joel was connected to the nest trap with a remote trigger to spring the trap when the bird was back on the nest.

We had already captured a loon that day without too much trouble, but now here was a challenge. The loon in question was not going back onto its nest. It was instead just a few feet offshore adjacent to the nest, swimming back and forth in short arcs right in front of the nest . . . but not touching shore.

Among those few who have followed them in the Western Arctic, yellow-bills are known to be highly sensitive and easily agitated. “It must see something,” I told Joel over the radio.

“Well, it isn’t me,” he said. I couldn’t see him, and with Joel reporting to be in a deep ditch in the tundra, absolutely out of sight, the plane on a different lake, and me a quarter mile away behind a low hill and hidden among the tall grass and mosquitos, effectively a quarter mile behind the loon, and the trap itself expertly camouflaged with carefully arranged grasses that the wind might have blown in, what could be keeping the bird off its nest?

I scanned the lake and the nearby tundra: absolutely nothing to keep the bird from returning to its incubation.

I watched a small group of caribou moving about through the scene near the nest. There was a sudden outburst over the radio—Joel was cursing me out for almost letting him get stepped on by the caribou. I told him that I was watching the loon; it was his job to avoid caribou. Fact was, I could not see him and had no idea where he was hiding.

When the caribou disappeared, I thought maybe they were the problem, but a half-hour passed and they were gone, and the loon was still swimming arcs just offshore of the nest. This long uncovered and unprotected, the loon eggs were wide open to the hunger of any of several avian predators.

“It must see something,” I told Joel. He remained silent, a patient trapper.

And then I had a thought based on my Common Loon experience: “It could be the plane,” I said into the radio. “Maybe we need to move the plane.”

“It’s on the other lake,” said Joel. The pilot, who had been overhearing our radio conversation, chipped in:

“It isn’t the airplane,” he said. “I’m sitting inside at about wing level and cannot even see your lake. The terrain between the lakes is high enough to completely block my vision.”

“I think we should move the plane,” I repeated.

“Wouldn’t that just scare the loon?” the pilot argued.

“He may not be able to see the nest lake from his seat in the airplane, but the tail fin (vertical stabilizer) on a Cessna extends well above the rest of the airplane, and this one is a big, tall rectangular bright electric yellow. I’m guessing it’s keeping the loon’s attention.”

Silence all around. Loon still paddling back and forth in front of the nest.

“Joel, I’m pretty sure the airplane needs to disappear,” I said softly into the radio. I felt an intense and certain privity now, a confidence throughout my being, about this presumption. And I felt an intense sharing and connection with Joel at that moment. If only he would trust me against his own doubts and the pilot’s. (In the Alaskan backcountry, you’re rarely allowed to argue against your pilot’s gut-feeling.) If I was correct, and I was convinced I was correct, I’d be saving Joel’s budget several thousand dollars for this wild loon chase—and a half day wasted.

Another ten minutes of silence. Then Joel addressed the pilot: “Uhhhhh, why don’t you take off and go check on the other trapping team….” I heard the Cessna engine start up, listened to it taxi across the neighboring lake, then the roar of take-off. Seconds later, I saw it arc over the distant tip of our nest lake and head off toward the crew to the west. When it was still visible, its roar fading toward silence halfway across our lake, I rolled over in the grass to look at our nest.

The loon was already back on its eggs.

“Fire when ready,” I radioed Joel.

“You sure it’s on the nest?”

“Affirmative. I’m looking at it.” Joel triggered the nest trap, resulting in a silent explosion of the grasses with which we had camouflaged the metal nest frame, and immediately thereafter with a loon suddenly struggling to take off against the soft netting. “You got it,” I said into the radio. Dr. Schmutz leapt into a full Ph.D. sprint to the nest to cover the loon with a large towel, settling it down until I could get there to help extract the bird.

“As soon as the plane left, that loon went back on,” I said quietly when I got there. Kneeling to help calm the surprised and frantic bird, I looked over at Joel. He was looking straight into my eyes, not with a disbelieving stare, but rather a simple question.

“How did you know?”

Twenty-five years of experience with Common Loons, I told him. My savvy was due to having observed this same behavior in commons when they are scared off the nest and their perceived threat remains in sight. This was precisely the kind of reason why he’d brought me here in the first place.

Twenty-five years of experience with Common Loons, I told him. My savvy was due to having observed this same behavior in commons when they are scared off the nest and their perceived threat remains in sight. This was precisely the kind of reason why he’d brought me here in the first place.

That evening, as we sat in front of our tent before turning in, I said to him, “I guess I earned my pay today—yes?”

“I’m not paying you,” he reminded me with his best deadpan frown. “You’re volunteering.”

I remember looking around us at the tundra and lakes, birdlife everywhere, the open blooming tundra with no end in any direction—the landscape itself was pay. Then there was my final hope to be a contributor to this study and the cost of all these flights, and equipment and the food and gear, not to mention the camaraderie among our small team. “Oh, you’re paying me alright,” I told him. “You already have.”

Jeff Fair

Lazy Mountain, Alaska,

Addendum:

Our study of the migrations of Yellow-billed Loons in the National Petroleum Reserve -Alaska lasted across a dozen summers and resulted in our discovery that nearly all of these birds did not fly along Alaska’s west coast to winter in Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska as was believed, but instead they migrated along a fairly straight line southwest to the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea off China to overwinter in those highly toxic waters. (It was the yellow-bills breeding on the western mainland of Canada that migrated southwest overland to overwinter in Prince William Sound and were affected by the Exon Valdez Oil Spill.)

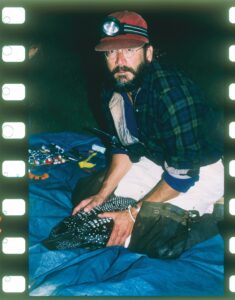

The loons we captured were weighed and measured extensively, banded with three color bands and one USFWS aluminum numbered band, and “marked” with a satellite transmitter that allowed Dr. Schmutz to closely follow every individual. We also collected a small amount of blood and a few specific feathers (clipped, not plucked) for later contaminant analyses; the feathers, formed during an overwinter molt on the wintering grounds would carry the record of their winter diets, and the blood would carry the same of their summer diet.

The yellow-bills in Alaska were declared “warranted but precluded” for Endangered Species Act listing in 2009 (precluded at the time due to the huge number of other nominated species). In 2014 with more data and consideration of a rather level population, they were found “not warranted.”

©️Jeff Fair 2023

Field Notes from a Backcountry Biologist

Homing Instinct

By the time I hired on to survey the Common Loon population of northern New Hampshire, back in 1978, Bald Eagles were long gone as a nesting species. Shot as predators, trapped for the taxidermy trade, left homeless as, one by one, their ancient nesting trees were sawed out from under them, and then poisoned inadvertently to the brink of extermination by insecticide, our national symbol had little reason to stick around. The last pair of Bald Eagles in New Hampshire had nested near the top of a huge old white pine tree near the western shore of Lake Umbagog. They laid their final clutch of eggs in 1949, then disappeared.

Years passed. Sometime in the late 1960s, that last eagle nest, long empty and derelict, tumbled out of its tree and crashed to the ground.

Years passed. Sometime in the late 1960s, that last eagle nest, long empty and derelict, tumbled out of its tree and crashed to the ground.

More years passed. Occasionally an eagle appeared near Lake Umbagog. Observations became more frequent. By 1981, I was spotting bald eagles during many of my surveys around the lakeshore, their white heads and tails glowing like spotlights against the dark alder and fir. Sometimes one would perch in the old “eagle tree.”

In 1987, a raptor biologist working on Lake Umbagog observed a Bald Eagles with a yellow tag in its wing. The tag identified the bird as a male abducted in 1984 from a nest in Alaska and released in New York State as part of the eastern recovery effort. He seemed quite willing to resettle here; by 1988 he was seen regularly in the company of an adult female. That was the summer I heard voices from a tree.

I was in my canoe near the shoreline of a quiet backwater, more than a mile from the lake and the eagle tree, searching for the nest of a pair of loons I had been tracking all summer. Suddenly, I heard the English language issuing forth from the top of a tall pine nearby. I paddled over to investigate. The tree became very quiet. After a few minutes, a human form descended the tree trunk. I observed that she was none too happy at being discovered.

Somewhat reluctantly she explained that a small team from the Audubon Society was constructing a nest replica to entice the new eagle pair. The tree seemed a safer site for a new eagle nest than the exposed top of a tree on the lakeside, where the team feared duck hunters might shoot the eagles, or (far more likely, I thought) birdwatchers might love them to distraction. Regardless, the initiative under way above us was an act of wildlife management, highly classified, and I was sworn to secrecy.

I never did find the loon nest, but late that summer we saw the eagles carrying sticks, and we knew something was happening. By the following spring they had finished installing a huge and ungainly pile of branches near the top of a tall white pine—not the same tree that had been chosen for them, but the very same tree where the last active eagle nesters had made their home in 1949.

I never did find the loon nest, but late that summer we saw the eagles carrying sticks, and we knew something was happening. By the following spring they had finished installing a huge and ungainly pile of branches near the top of a tall white pine—not the same tree that had been chosen for them, but the very same tree where the last active eagle nesters had made their home in 1949.

How did a young eagle, hatched a continent away and belonging to a species that had not nested in these parts in four decades, come to choose the eagle tree? We may never know the answer. It is enough for now to observe, in a time of population modeling and species management, that these patterns of resilience of hope itself, are carried within the individual: a young eagle, an ancient pine, perhaps even a dutiful field biologist, kneeling in his canoe.

Jeff Fair

Lazy Mountain, Alaska

Jeff Fair has visited New Hampshire’s Lake Umbagog every year since 1978 to count loons and listen for voices in the trees.

This essay was originally published in Natural History Magazine, February 2003, and reprinted here with permission.

Eagle photos by Sharon Fiedler

The Call of the Northwoods

The call of the Northwoods? Yes, but which one? Which woodnotes, what northern soundtracks best inform our images and reflect our romance of the Great Northwoods? In my case the list ranges from the classic to what some might consider the obscure: The midnight falsetto of loons. The dissonant harmonies of wolves. That old hoot-owl down on Tidswell Point. The motor-like whine of a quadrillion mosquitoes lifting out of the willows in dinner formation. Wind whipping through the pines. The hollow winnowing of snipe. One white-throated sparrow chanting his Old Sam Peabody Peabody Peabody mantra.  The bellow, come September, of a rutting bull moose, which sounds as though someone were prying open the corroded door hinges of a rusted-out 1967 Dodge Power Wagon. The deep-throated, urgent peals of the mink frog, Rana septentrionalis, “frog of the North,” so rarely acknowledged by my bird-watcher friends. Only the conversations of trout are less discerned. I love them all.

The bellow, come September, of a rutting bull moose, which sounds as though someone were prying open the corroded door hinges of a rusted-out 1967 Dodge Power Wagon. The deep-throated, urgent peals of the mink frog, Rana septentrionalis, “frog of the North,” so rarely acknowledged by my bird-watcher friends. Only the conversations of trout are less discerned. I love them all.

Yet there is another suite of Northwooden sounds just as memorable and appropriate, but which lie outside the purview of this volume—except that I shall invoke a few examples here, to wit: That lovely cadence, echoing from afar, of someone splitting spruce rounds with an axe for her evening fire. Rain—or black flies—ticking against the brim of a felt fedora. The voices of Hastings and Ricardi and their guitars—In the midnight moonlight midnight—mixed with the crackle and splendor of their bonfire, all softly muffled by the surrounding forest. The preprandial clatter and swearing—“Ouch! Hah-damn dat’s hot!”—of my friend Armand Riendeau out by his fire pit on the Rapid River in Maine, as he prepared his infamous poisson fumé avec sauce au brocoli (yellow perch smoked above his campfire in the housing of a discarded water heater with a can of condensed soup for marinade). Like other old-time guides and cooks of the Great Northwoods, Armand is gone now. He was an endangered species when I knew him, rarer than the Kirtland’s wobbler he told me once himself.

And . . . that faint drumming from out across the lake of a trip of canoes paddling in the still of night after spending the day windbound. My own intimate romance of the Northwoods was kindled four decades ago in my earlier, more formative years (all my years are formative years) by this very sound on a dark July night in New York’s Adirondack State Park. Two other staff men and I and nine campers from a venerable canoe camp over in Vermont (wood-canvas canoes, traditional Cree paddling techniques, etc.) had established ourselves on the shore of Waltonian Island. Late in the evening the two senior staff took it upon themselves to paddle to the mainland on a venture about which I was sworn to secrecy (though I still remember the women’s names), leaving me on watch. The night was still, and I let our fire burn down to a few incandescent coals.

And . . . that faint drumming from out across the lake of a trip of canoes paddling in the still of night after spending the day windbound. My own intimate romance of the Northwoods was kindled four decades ago in my earlier, more formative years (all my years are formative years) by this very sound on a dark July night in New York’s Adirondack State Park. Two other staff men and I and nine campers from a venerable canoe camp over in Vermont (wood-canvas canoes, traditional Cree paddling techniques, etc.) had established ourselves on the shore of Waltonian Island. Late in the evening the two senior staff took it upon themselves to paddle to the mainland on a venture about which I was sworn to secrecy (though I still remember the women’s names), leaving me on watch. The night was still, and I let our fire burn down to a few incandescent coals.

Out on the water I heard something, barely audible a first, not a whisper but a heartbeat. The syncopated drumming grew closer, and I soon recognized it as the sound of the two paddlers returning, the shafts of their paddles bumping the gunnels of their canoes with every stroke in true Cree style. Ash to ash, wood to wood, wooden paddle to wooden canoe—the heartbeat on the water. In that moment I came to know that humankind once was and can still be a natural and organic part of these Northwoods, of the real world, wild and beatific.

Twenty years passed, and then one night in a secret and solitary campsite on the shore of Aziscohos Lake in western Maine, I awoke to that same heartbeat again, this time accompanied by the lively tune of a fiddler in one of the canoes. I sat in silence and listened, mesmerized, as the ash and fiddle corps’ music carried across the water for miles. Years later, as I was telling this story, my brand-new friend Bill Zinny would ask, “Was it Saint Anne’s Reel?” When I replied Yes, he said, “That was me.”

The moral I labor toward is that we need not look past our own kind for some of what calls us back to the Northwoods. In fact, until enough of us remember that we are part and participant of the landscapes we love, until we remember how to approach them with respect and reverence, with joy and appreciation and music—there will be no true land ethic, no complete conservation. Participation involves knowledge and understanding, something available from experience, a grandfather, or a field guide. But it also requires an intimate connection, a willingness and desire to romance the land and those who dwell there. That part, dear reader, is up to you.

One more thing. The authors of the little Northwoods primer I’d written this foreword for needed also to limit their geographic purview, but the reader and I do not, and much to be found in the natural history of the northern forest of Maine is applicable far and wide across the northern forests of this continent. For example, here by the Matanuska River in southcentral Alaska, on a distant edge of the boreal forest, I live among spruce and birch, cottonwood and aspen and alder, mountain ash and highbush cranberry, fool hen and hare and hoot owl, red-backed vole and moose and bear. Far away in miles, but not much different in content and spirit from Sigurd Olson’s Northwoods, nor Robert Frost’s.

These woods, too, bring me joy. This afternoon, while the sunset lingered in hot pink and salmon and violet low in the southwestern sky, I watched the ravens wing their way, croaking and clanking, back to a secret roost in the high country. A buzz of boreal chickadees has reappeared at my suet. The ermine who lived with me last winter has moved back under my cabin; I found his signature on the snow today. Now, in the final twilight, that same old fool moon sleds low across Pioneer Peak, silhouetting the steepled spruce and breaking trail for Orion. And what I am privileged to listen to at this moment is the hush of the hoarfrost, the music of the stars—a profound and crystalline silence. One more song not to be found in the field guides, but valid to the human heart as a reminder of a peace, wild and primeval, available to us in the dark and lovely woods. Wherever we may find them.

Jeff Fair,

Lazy Mountain, Alaska

This essay was adapted from the Foreword to The Call of the Northwoods by David Evers and Kate Taylor, 2008, Willow Creek Press.

Illustrations by Shearon Murphy

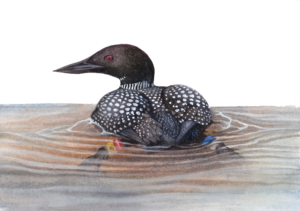

Call of the Loon

When I first began working with loons as a young wildlife biologist in the summer of 1978, my research vessel was a 17-foot canoe. For the larger lakes I would borrow whatever motor craft was available, usually a crooked aluminum derelict of one brand or another with a retired and ill-tempered two-cycle kicker bolted to its transom, a rusted toolbox in the bilge containing no wrench and the wrong-sized spark plugs, and a cement-filled coffee can with no anchor line. Those were the days.

My primary tools aside from the vessel and a sodden 20-pound kapok life vest, which I used for a seat cushion, were my Sears 7×35 extra wide-angle binoculars, a pocket-sized notebook, and three knife-sharpened No. 2 pencil stubs. (The latter two constituted my “iPad,” then and now; largely hands-free, floatable if dropped, nonrunning penciled notes if soaked, batteries not needed, etc.) I spent a lot of time alone on the water, watching the loons. It was a good job. Didn’t pay much, but I enjoyed the open sky and learned a lot.

Looking back, those really do seem like the good old days. They might also be called the Dark Ages. The body of scientific loon literature was pretty small back then. Our basic field library could be carried in a single pocket and consisted of a copy of Dr. Judith McIntyre’s Ph.D. dissertation, Biology and Behavior of the Common Loon (printed from microfilm in small format and bound with a black cover, giving the loon biologist the look, at times, of a waterborne evangelist consulting the scriptures), and a tertiary water-blurred photocopy of The Common Loon in Minnesota (Olson and Marshall, 1952—the year I was born). No one knew much about loons back then, but as I say, we were learning.

Looking back, those really do seem like the good old days. They might also be called the Dark Ages. The body of scientific loon literature was pretty small back then. Our basic field library could be carried in a single pocket and consisted of a copy of Dr. Judith McIntyre’s Ph.D. dissertation, Biology and Behavior of the Common Loon (printed from microfilm in small format and bound with a black cover, giving the loon biologist the look, at times, of a waterborne evangelist consulting the scriptures), and a tertiary water-blurred photocopy of The Common Loon in Minnesota (Olson and Marshall, 1952—the year I was born). No one knew much about loons back then, but as I say, we were learning.

Much as I appreciate all that we learn about loons from our more complex scientific approaches these days, I’m glad that I was able to begin my work in the old-fashioned realm of naturalistic observation, simply watching objectively and getting to know the birds and the variations of their behaviors a little better, much as a good hunter knows his deer and the fisherwoman her trout. Of course, as loon science matured, the research grew more sophisticated, more complex and expensive, employing higher technologies and more invasive techniques than I cared to mess with. This included the invention of a technique for the regular capture of loons to mark them so that we might monitor the lives of individual loons and pairs. I recognized this as a major breakthrough in our studies of loon demography, toxin loading, and more—but I retained a personal disinclination toward handling these creatures of mystery and wildness. Plucking them out of their innocent careers, likely scaring hell out of them, and then releasing them to be forever outed seemed disrespectful, I thought.

That was 34 years ago, but even back then I realized that we had to know more—have more proven facts—about the loons’ plight in order to fight against their disappearance, in order to conserve the species. This was not a moral need, but rather a political one. It seemed to me then and still does today that if we know we’re poisoning a natural biosystem, it is only sensible, logical, ethical to stop polluting it. But the world in its modern, advanced state didn’t work that way.

So, I kept my boots in the water; might as well be part of the answer rather than running off to hide. I even netted a few birds myself, and then became proficient at it. But the application of those higher technologies (blood and feather sample and analyses, prolonged handling to take dozens of measurements, statistical machinations with the data, even the small encumbrance of tarsal bands) seemed antithetical to the loons’ wild mystique. I remained skeptical.

Then one July night two decades ago, I learned another lesson. I was riding back from several days of loon surveys on Chesuncook Lake in Maine in biologist Bill Hanson’s truck with a tight, seaworthy boat in tow, when his cell phone rang. Another research crew had observed a loon with a fishing lure impaled in its bill over on Wyman Lake, not far out of our way. It was a pathetic sight, the loon appeared weakened and staying in one area, and they believed they might be able to capture it and remove the hardware so that it could eat again. But they could use a second boat, a few more hands. The plan was to rendezvous at a remote boat landing just after dark.

Later, as our rescue flotilla motored out onto the dark lake, I thought of how many situations like this I’d seen in Maine and New Hampshire before we had a technique to capture a bird so afflicted. How we could only chase them or watch them struggle—and how so many of them must have died an agonizing death of starvation and drowning. Now our proven capture technique might effect a rescue, a humane and altruistic act unrelated to our scientific endeavor (or so it seemed).

Three powerful spotlight beams clicked on and panned across the water. Recorded loon calls broke the silence to attract our quarry. Someone called out; our boat approached the victim. Closer . . . a net flourished off the bow and the loon was in our custody.

We wrapped it in a towel, carefully pried open its bill, and inspected the damage. Two-thirds of a huge, shiny treble-hook were driven right down through the center of the bird’s tongue, protruding through the bottom and displaying ugly barbs intended for a fish’s mouth. Under the lights of headlamps and with hemostats and wire cutters we carefully clipped off the embedded trebles, freed that spirit of its hideous impediment, and released it onto the black water and into the night. We sat quietly for a while out there, allowing peace to descend, and then motored back to reassemble on shore and celebrate our success in the ambient starlight.

Why do we study loons? I believe there is more to it than scientific or political needs for data and answers. We learn about loons because we are curious about the things we love, because knowledge leads to a deeper intimacy, a stronger connection to the objects of our affection. For me, the first and primary question to any gatherer of truths is not “What have you found?” but rather “Why have you come here?” Few wildlife biologists that I know entered their field of study in order to answer a particular scientific quandary. They come first to fulfill a desire to be closer to the wild spirits—of the wild creatures themselves, or of a chosen landscape.

Why do we study loons? I believe there is more to it than scientific or political needs for data and answers. We learn about loons because we are curious about the things we love, because knowledge leads to a deeper intimacy, a stronger connection to the objects of our affection. For me, the first and primary question to any gatherer of truths is not “What have you found?” but rather “Why have you come here?” Few wildlife biologists that I know entered their field of study in order to answer a particular scientific quandary. They come first to fulfill a desire to be closer to the wild spirits—of the wild creatures themselves, or of a chosen landscape.

“You can do the best science in the world but unless emotion is involved it’s not really very relevant. Conservation is based on emotion. It comes from the heart, and one should never forget that,” wrote Dr. George Schaller.

And this is what brings us all together—field biologist, scientific research technician, curious reader, and interested observer—this desire for intimacy with the magic of the real world. And what the resultant inspired knowledge leads to, when shared, is the opportunity for all of us together to help free the loons from entanglement in our modern web of hardware and technologies, from poisons, fishing tackle, and in the end—best of all—from the pall of misunderstanding and ignorance. And if we can do that for the loons, my God—think what we could do for ourselves.

That is what we drank to on Caratunk Landing that night as we listened to the wails of a newly unencumbered spirit out there in the starlit darkness. We weren’t just celebrating the loon’s revival.

We were celebrating our own.

Jeff Fair,

Lazy Mountain, Alaska

This essay was adapted from Jeff’s foreword to the Call of the Loon by David Evers and Kate Taylor, 2006, Willow Creek Press

Illustrations by Linda Mirabile, RavenMark

Backcountry Beginnings: Early Luck

by Jeff Fair

It was the middle of May 1976. I was looking for a job to follow up on my MS in wildlife ecology work at the University of New Hampshire. I had filled out exactly 98 U.S. government application Standard Forms 171 and sent them off to every Rocky Mountain national wildlife refuge, park, and forest, plus one exception. I had a contact at Colorado State who sent me a job announcement from the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, an association of agencies and universities covering the Yellowstone area and run by the National Park Service. The notice offered two seasonal positions—one for reconnaissance for grizzly presence or sign, and one for vegetation analysis in areas of grizzly activity—and it specified that it would only hire applicants from the Intermountain Region. Successful applicants were to be contacted in March.

I ignored the geographic exclusion and mailed in my 99th application. I knew it was a long shot. March and April came and passed with no takers. Zero out of 99; I was rather despondent. Then late one evening in May, my phone rang. It was Steve Judd in Yellowstone, number-two leader of the study team.

“You still looking for work?”

“Yes, sir.” I felt as though my feet were floating six inches off the ground.

“Well, it says here you preferred reconnaissance, but our recon team is all on horseback, and you being from Pennsylvania and New Hampshire, I don’t think you know [crap] about horses.”

“I’m a fast learner,” I said.

“Not fast enough.”

“OK,” I said, “I’ll take the veg crew.”

“I don’t have any openings in the veg crew. How would you like to trap?”

I was now in the clouds. Trapping grizzlies in Yellowstone to radio-collar them was the apotheosis of my wildlife dreams. Ever since I was a kid, I’d watched the Craighead brothers on TV collaring and tracking grizzlies in Yellowstone. I had no idea that my application would lead to this level of participation.

Of course, it was blind luck (serendipity) on my part. It turned out that for my study of white-tailed deer at the University of New Hampshire, I was using an experimental tranquilizing drug mixture that happened to be the exact same mix the grizzly team was using on bears. (The mix of two drugs, one with an antidote, allowed for a quicker take-down—less chance of injury by deer or a run-off by a bear—and a quicker recovery with the same benefits by cutting the dosage in half via one drug’s antidote.) And they were avoiding the risk of overdosing and killing a Yellowstone grizzly by hiring a young biologist, even from across the continent, who had experience with the mixture on a large mammal.

That summer spoiled me for life. I soaked in the Rocky Mountain wilderness. I was already developing my affinity for the big wild country. Meanwhile, my partner and I trapped and collared two grizz (one of them the Craigheads’ old Number 13) down by Yellowstone Lake. Success!

But no more Ph.D. dreams—I wanted the field work, as backcountry as I could get. For the rest of my life, whenever the fluorescent-lit cubicles and piles of paperwork crowded in on me, I promoted my boots and myself back into the field. I was lucky again and again with my timing, moving from Yellowstone to Utah (game biologist and warden: one career arrest) to New Hampshire and Maine and the loon work (a job I first took not for the loons, but simply to get north from Oklahoma) and eventually to Alaska, the mother lode of backcountry, wolves, five species of loons, and three of bears. I’ve lived here ever since, hitchhiking by float plane and for some jobs by jet to many distant outposts. It hasn’t been a profitable career financially, but it offered the treasure of living my passion.

What’s so different, so enticing about the backcountry experience to me? I like the solitude, the silence, the quiet joy of equal-minded camaraderie among a very small society in a wild expanse, and when I get out of earshot, that primeval white-noise soundtrack of wind and river and wilderness. I like the musical inspiration of that voice that narrates my life when I’m in a place where it feels like the dawn of creation. A good biologist—a studier and recorder of life—has clearer insight and does much better at observing and mindfulness when they are working, participating, in the landscape they love. And I like the existential magic that can occur out there when I escape the busy, clattering, and cluttered downtown world. Yes, magic. Nearly inexplicable yet real phenomena. What follows is an example of that backcountry magic that reaches beyond normal science [1]:

Five of us were coursing through the dark in an open skiff one moonless, late-summer night a few years ago. This was a large northern lake in the High Northeast, the air was sodden and cool, and our velocity through the darkness enlivening. My companions had invited me along as guide. After 20 years of observing the Common Loons who live here, I had a good idea where they and the rocks might be hiding.

Five of us were coursing through the dark in an open skiff one moonless, late-summer night a few years ago. This was a large northern lake in the High Northeast, the air was sodden and cool, and our velocity through the darkness enlivening. My companions had invited me along as guide. After 20 years of observing the Common Loons who live here, I had a good idea where they and the rocks might be hiding.

Our purpose was to capture loons and adorn them with bracelets—two colored bands on each foot in unique combinations—so that researchers could recognize individual birds and thereby learn something more of the culture and habits of these creatures. With the subjects in hand, we would also collect two secondary wing feathers and a tiny sample of blood for toxicological analyses. Blood samples show what toxins the birds are consuming there on the breeding grounds. Flight feathers are manufactured in coastal winter retreats and carry poisons from the sea.

Leading our venture that night was Dr. David Evers, who had invented the technique we would use to catch our quarry. The safe and practical capture of loons had been considered impossible for decades. Then along came Evers, the proverbial unenlightened grad student, ignorant of the impossibility. He pieced together two other techniques involving spotlighting, recorded loon calls, and oversized landing nets, added a twist of his own, and to date has orchestrated the capture and release unharmed of thousands of loons.

While I recognize the plight of loons—their ecological balance skewed by the heavy thumb of human industry, and the need for greater biological understanding of their lives—deceiving them with false cries and blinding lights seems somehow disrespectful. The idea of holding, in callused human hands, these wild spirits of the north woods vexes me, and one of the reasons I’d come along this night was to certify firsthand my companions’ respectful handling of them. But I had other reasons. I find a deep satisfaction in knowing my way around a lake at night under starlight alone and by horizons only visible in the periphery when you look away from them. I treasure knowing these birds well enough to call on them in such an intimate fashion. It is this, and not science, that brings me joy.

After a quarter century of poking about the backcountry as a wildlife biologist, I had come to recognize that science alone cannot come near to fully informing our understanding of the wondrous world. I depend on the scientific process and believe in it—but only so far as it reaches. I know, too, that beyond the simple, certain beauty of objective observation and scientific technique lurks an intractable, immeasurable world of knowing—far outside the ken of statistical evaluation, yet real as the stars, a hunter’s intuition, the curiosity of a child. I often wonder who among my fellow biologists allow themselves to embrace the magic, and I carry a certain distrust for those who ignore or deny it.

We had caught and banded four loons that night when things began to slow down. It was hours after midnight, the chill had penetrated us, and the ghosts had returned—those weird, cyclonic wraiths of steam arising from the warm lake surface like pillars—invisible under starlight but solid and opaque as concrete in the beam of million-candlepower technology. We were weary and worn-out, and had just been stood up by the Glassby Cove Pair, who hovered 75 feet away, illuminated but untouchable. We shut off the spotlights to discuss strategy.

In the final dimness of the last fading beam, I saw one of the pair dive. At that very moment I experienced an odd and unexpected privity, a confidence that the diving bird was swimming toward us and would surface next to me. Under cover of darkness, while the others chatted, I poised my net near the water.

Seconds later the loon broke the surface beside me and, fully prepared, I slid the net under it. As I delivered that delicate spirit out of the night and over the gunnel, headlamps lit up, data sheets and wire rings of multicolored bands appeared, while whispered voices exclaimed in disbelief.

Myself, I felt exhilaration more than surprise. Exhilaration born of intimacy, however brief.

“I just knew it was going to be there . . .,” I explained to Evers, the only silent member on board. Looking up for only a moment from the sampling kit he was opening on his lap, he grinned serenely.

“I know,” he said.

In 1992, Jeff Fair began his collaboration with David Evers to band loons on Northeast lakes. In 1996, they established a research station in Rangeley, Maine, where crews have been monitoring local loon populations ever since.

[1] I first published a version of this field note in the journal Wild Earth in the fall of 2002.

Illustrations by Shearon Murphy

Photo Credits: Header photo © Shearon Murphy