Research on Block Island

Approximately 13 miles off the southern coast of Rhode Island in Narragansett Bay lies a teardrop-shaped natural wonder: Block Island. In the fall, countless numbers of migrating birds stop at Block Island to rest and refuel before continuing their journeys to distant southern latitudes. Often times, their destinations are thousands of miles away in Central and South America.

Migration can be a long and arduous endeavor for birds, and their survival during this journey can have a strong effect on overall populations. Researchers have known for years that Block Island is an ideal place to study songbirds during migration. Only recently however, did we confirm that Block Island is also highly valuable for studying migrating raptors.

Overview

BRI biologists established a raptor research station on Block Island during the autumn seasons of 2012 and 2013 with the help of The Nature Conservancy. From that station, we captured, banded, and collected blood and feather samples from migrating raptors.

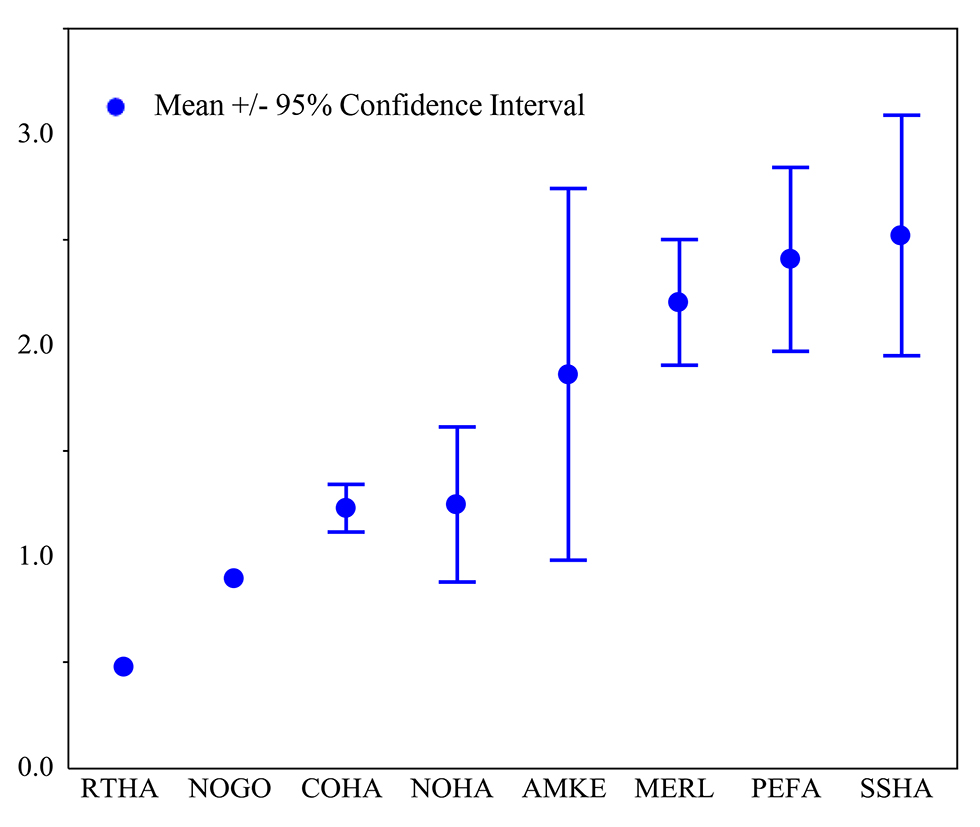

In the first two seasons, we captured 263 individuals of 8 different raptor species; the most commonly observed and captured being Merlins and Peregrine Falcons. We encountered Northern Harriers, Cooper’s Hawks, and Sharp-shinned Hawks with moderate frequency, and rarely captured American Kestrels, Red-tailed Hawks, and Northern Goshawks.

The suite of species we encountered on Block Island was expected because their body design (wing shape and bird weight) influences their willingness and ability to embark upon large open water journeys to offshore islands.

Raptors as Bioindicators

Scientists have been using raptors as barometers of ecosystem health for decades. Their distribution and abundance are closely tied to the food webs that support them. Raptors often sit at or near the top of those food webs and tend to accumulate contaminants from prey; their tissues (blood, feather, or eggs) are regularly used to monitor contaminants in our environment.

Several raptors, such as Bald Eagles, Peregrine Falcons, and others, were nearly extirpated due to contaminant exposure and other factors. As a result, these species’ natural histories are closely intertwined with some of the most important landmark environmental policies in U.S. history, such as the banning of DDT and the Endangered Species Act.

Learning about Raptor Movements Using Satellite Telemetry

Some raptors such as Peregrine Falcons have been observed over a thousand miles offshore, but such movements were poorly documented until recently. Recent advances in animal tracking technology have allowed researchers to collect information on the migratory patterns of birds at a scale that was previously unthinkable: globally.

By fitting birds with small backpack-mounted tracking units, we can study their daily and annual movements, flight altitude, and other information. This information is critical in providing background information critical to numerous management and conservation issues, such as evaluating the potential conflicts between migrant raptors and offshore wind energy facilities.

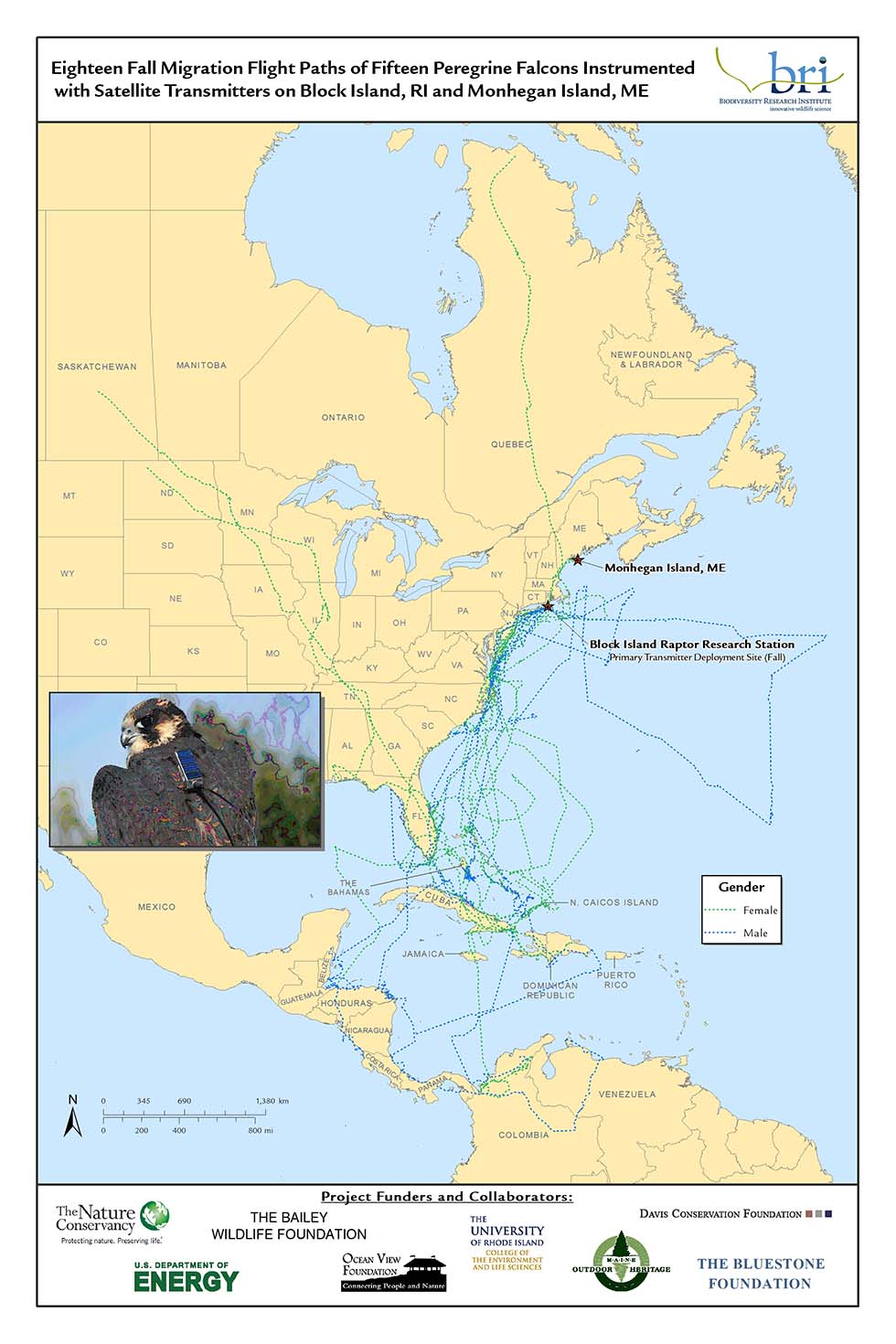

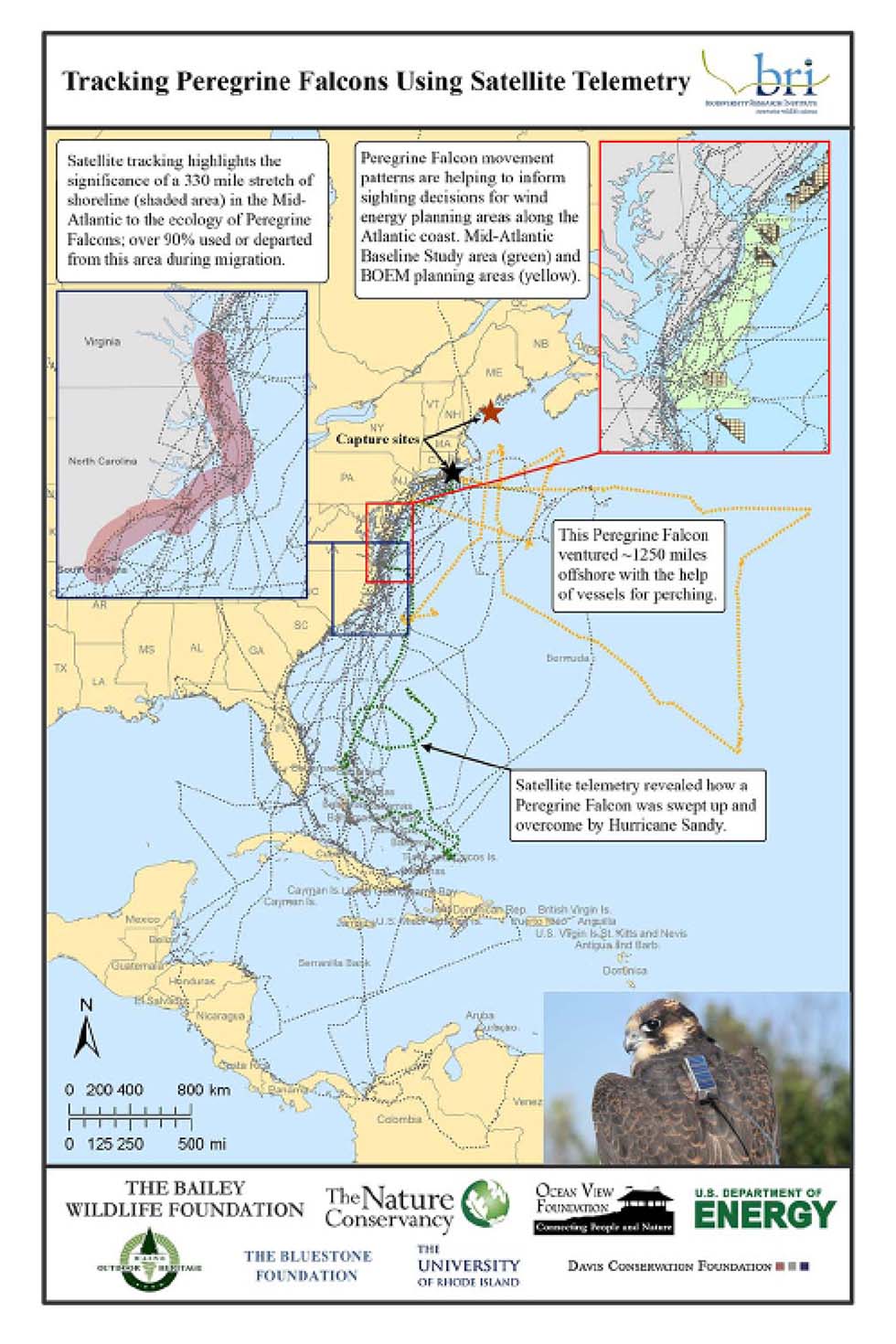

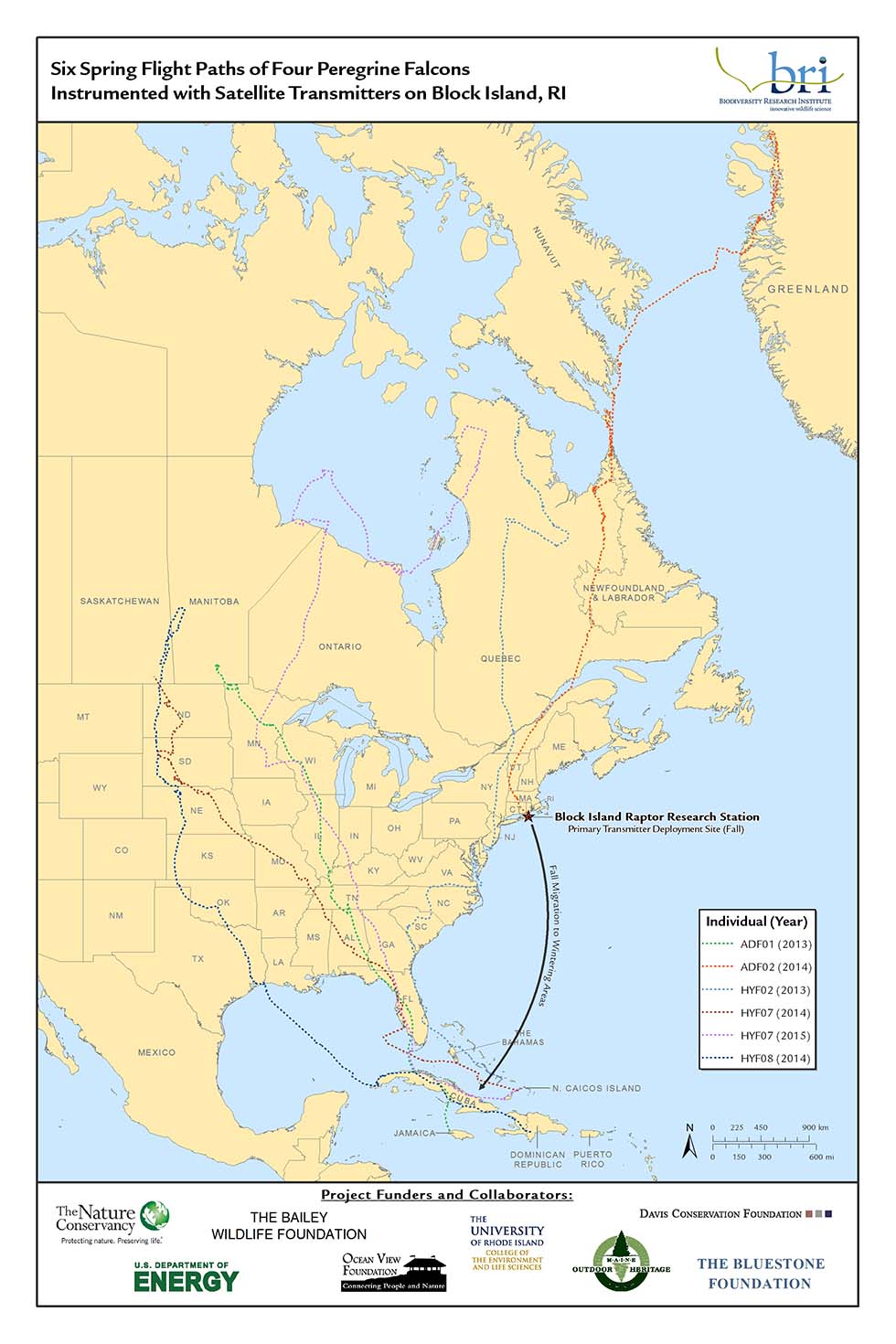

Over the fall seasons of 2012-2015, we fit satellite tracking units to thirteen female and nine male Peregrine Falcons. We were interested in determining where they overwintered, where they came from, which migratory routes and habitats they used throughout their migration, and the extent to which they used proposed offshore wind energy areas in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. Falcons fitted with transmitters on Block Island, RI, and Monhegan Island, ME, were successfully linked to wintering areas throughout the Caribbean and Central and South America (see Map 1). The majority of migrant peregrines initiated trans-oceanic flights from a stretch of shoreline spanning between Cape Charles, VA, and Cape Fear, NC, and tracked peregrines revealed several other fascinating habits such as barge-riding in the mid-Atlantic and iceberg-riding in Hudson Bay (see Map 2).

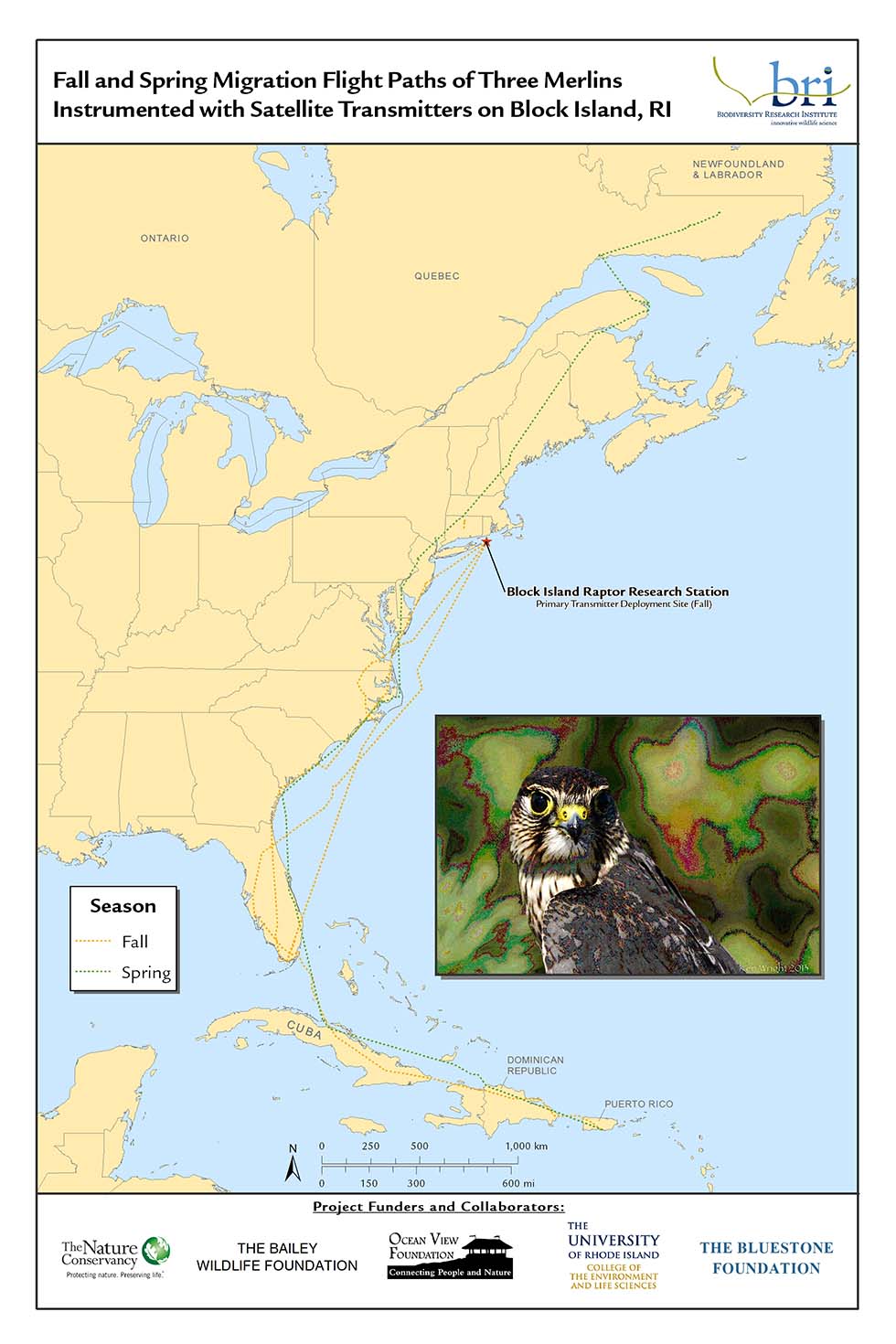

After their first winter, several individuals were tracked to Saskatchewan, Manitoba, northern Quebec, Ontario, and Greenland (see Map 3). We also established fall and spring migration routes of Merlins, whose habits during migration are poorly understood (see Map 4). Many of these satellite-tracked raptors continue to provide information important to our understanding of migration ecology, which is critical to conservation efforts.

Map 1 (left): Eighteen Fall Migration Flight Paths of Fifteen Peregrine Falcons Instrumented with Satellite Transmitters on Block Island, RI and Monhegan Island, ME (2012-2014). Map 2 (right): Tracking Peregrine Falcons using Satellite Telemetry: Highlights (2012-2014). Hyperlinks to download these maps are below.

Map 3 (left): Six Spring Flight Paths of Four Peregrine Falcons Instrumented with Satellite Transmitters on Block Island, RI (2012-2014). Map 4 (right): Fall and Spring Migration Flight Paths of Three Merlins Instrumented with Satellite Transmitters on Block Island, RI (2014). Hyperlinks to download these maps are below.

Evaluating Mercury Exposure in Migrant Raptors

BRI researchers have been measuring mercury exposure and impacts in birds for more than two decades. Mercury, a naturally occurring element, is released into the environment through a wide variety of industrial processes, such as coal burning and gold mining. Mercury is persistent and quickly accumulates in organisms, magnifying up food webs, placing top predators at risk. Species have different sensitivity levels to mercury exposure, and mercury’s potential effects on some populations remain poorly understood.

Traditionally, toxicologists focused on evaluating contaminant exposure in fish-eating birds such as Bald Eagles. Recent studies, however, show that birds feeding in terrestrial food webs, such as songbirds (and thus their predators), are at equal or greater risk to mercury effects. Due to increased concerns that global mercury emissions are rising, researchers are interested in measuring current mercury exposure across species and regions.

Figure 1. Mean breast feather mercury concentrations in eight migrant raptor species captured on Block Island, fall 2012-2013. Mercury concentrations in migrant raptors sampled at Block Island showed differences in exposure by species. Sharp-shinned Hawks had the highest concentrations, while Red-tailed Hawks had the lowest. While these exposure levels are low compared to other well-studied raptors such as Bald Eagles, recent studies suggest that some species may be more sensitive to mercury than previously though

Future Research Plans

The Block Island Raptor Research Station is the northernmost and furthest offshore on the Atlantic coast. These characteristics, coupled with the unique migration patterns of raptors there, make this island valuable to the scientific community for its research and monitoring potential.

The station has enabled BRI researchers to gather one of the most comprehensive datasets on migration routes used by Peregrine Falcons along the Atlantic Flyway. Information on migration patterns helps us better understand the migratory ecology of species and has a wide variety of conservation and management applications, such as linking breeding and wintering populations and identifying important stopover habitats.

Peregrine tracking data was a component of BRI’s Mid-Atlantic Baseline Study, which aims to improve our understanding of wildlife use patterns relative to wind energy facilities proposed in the Mid-Atlantic U.S.

We are building our sample size of satellite-tracked Peregrine Falcons and further expanding tracking efforts to focus on other species such as Merlins and Northern Harriers, both of which are poorly studied. We will continue banding and collecting biological samples from raptors to evaluate their exposure to mercury as well as other contaminants. And, we will use the Block Island Raptor Research Station to conduct educational outreach efforts focusing on raptors, conservation, and environmental issues. Sustaining operation of this research station will enable further development of other studies with additional partners to maximize overall conservation benefits of this work.

Downloads

Download our Science Communications Brochure:

Desorbo, C. R. 2014. Raptor Research on Block Island. Biodiversity Research Institute. Portland, Maine. Science Communications Series BRI 2013-23. 6 pp.

Download Mid-Atlantic Baseline Study report chapter, submitted to the Department of Energy:

Desorbo C.R., R.B Gray, J. Tash, C.E. Gray, K.A. Williams, D. Riordan. 2015. Offshore migration of Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) along the Atlantic Flyway. In: Wildlife Densities and Habitat Use Across Temporal and Spatial Scales on the Mid-Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf: Final Report to the Department of Energy EERE Wind & Water Power Technologies Office. Williams KA, Connelly EE, Johnson SM, Stenhouse IJ (eds.) Award Number: DE-EE0005362. Report BRI 2015-11, Biodiversity Research Institute, Portland, Maine. 31 pp.

DeSorbo, C.R., L. Gilpatrick, C. Persico, and W. Hanson. 2018. Pilot Study: Establishing a migrant raptor research station at the Naval and Telecommunications Area Master Station Atlantic Detachment Cutler, Cutler Maine. Submitted to: Naval Facilitates Air Force Command (NAFAC) PWD-ME, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Biodiversity Research Institute, Portland, Maine. 6 pp

Related page: Characterizing the Diurnal and Nocturnal Raptor Migration at Monhegan Island, Maine

Download Map 2:

Tracking Peregrine Falcons using Satellite Telemetry: Highlights (2012-2014).

Download Map 3:

Six Spring Flight Paths of Four Peregrine Falcons Instrumented with Satellite Transmitters on Block Island, RI (2012-2014).

Download Map 4:

Fall and Spring Migration Flight Paths of Three Merlins Instrumented with Satellite Transmitters on Block Island, RI (2014).

Collaboration and Funding Support

- The Nature Conservancy

- The University of Rhode Island, College of the Environment and Life Sciences

- Ocean View Foundation

- U.S. Department of Energy

- The Bailey Wildlife Foundation

- The Bluestone Foundation

- The Overlook Foundation

Photo Credits:Peregrine Falcon © BRI – Chris Persico; Northern Harrier © BRI – Chris Persico; Juvenile male Peregrine Falcon © BRI – Rick Gray; Biologist Rick Gray with raptor © BRI – Chris Persico; Mercury graphic © BRI; Measuring a Cooper’s Hawk © BRI – Rick Gray; Peregrine Falcon Ken Archer; American Kestrel © BRI – Rick Gray