A Whale of an Idea: BRI Launches its Marine Mammal Program

By Eleanor Eckel, MELP, Online Communications Manager; Science Policy Coordinator

The ocean covers approximately 70 percent of Earth’s surface and is the largest livable space on our planet. Deep below there exists a realm inhabited by a wide variety of marine mammals—whales, dolphins, porpoises, seals, sea lions, and manatees—that embody a mysterious and profound connection to cultures worldwide. Marine mammals are spiritual symbols, sources of sustenance, and top predators that play a crucial role in the ecosystem of the ocean.

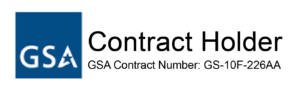

Focal species for the program include whales, dolphins, porpoises, seals, sea lions, and manatees. Photo of harbor seal by J. Stepanuk.

Unfortunately, dumping tons of plastics overboard, overfishing, industrial pollution, and increased boat traffic have introduced a litany of stressors into our marine environments, from disruptive noise to toxic contaminants. Furthermore, alterations in oceanic conditions spurred by climate change pose additional challenges, impacting the delicate balance of predator-prey dynamics and influencing important aspects of marine mammal biology, including reproductive success and population distributions.

Recognizing the urgent need for comprehensive research and conservation efforts, BRI recently launched its Marine Mammal Program. Co-directors Julia Stepanuk, Ph.D., and Megan Ferguson, Ph.D., have been at BRI for less than two years, but with decades of experience observing and researching marine mammals all over the world, they have hit the ground running. Together, they lead a multidisciplinary team that aims to unravel the complexities of marine mammal ecology and address emerging threats to their populations to better aid conservation efforts.

The program’s staff are highly skilled in a variety of ocean research methods, including visual and digital aerial and vessel-based surveys, acoustic monitoring, marine spatial planning, and ecological forecasting, among others. Through rigorous fieldwork, data analysis, and dissemination of research findings, these biologists provide critical insights necessary for the effective management and conservation of marine mammal species.

There are many species of dolphins and other marine mammals that we know very little about. BRI’s marine mammal team is working to change that. Photo by J. Stepanuk.

Despite the newness of the program, BRI’s interest in marine mammals actually began nearly two decades ago when David Evers and Kate Taylor embarked on a transformative expedition with the Ocean Alliance (see box below), collaborating with its founder and renowned marine biologist Dr. Roger Payne. This expedition, during which samples and data on global pollutants were collected from sperm whales, planted a seed that would ultimately lead to the formation of BRI’s Marine Mammal Program.

Though still in its infancy, the breadth and scope of knowledge of the program’s staff and BRI’s commitment to “assess emerging threats to wildlife and ecosystems through collaborative research” inspires confidence that this program will tackle urgent threats to marine mammals head on.

Related Links:

Information about mercury in marine mammals can be found in this publication by BRI.

Marine Mammal Program

Center for Conservation and Climate Change

Dynamic Duo Brave High Seas for High Stakes

Dynamic Duo Brave High Seas for High Stakes

By Sarah Dodgin, M.S., Ecological Analyst

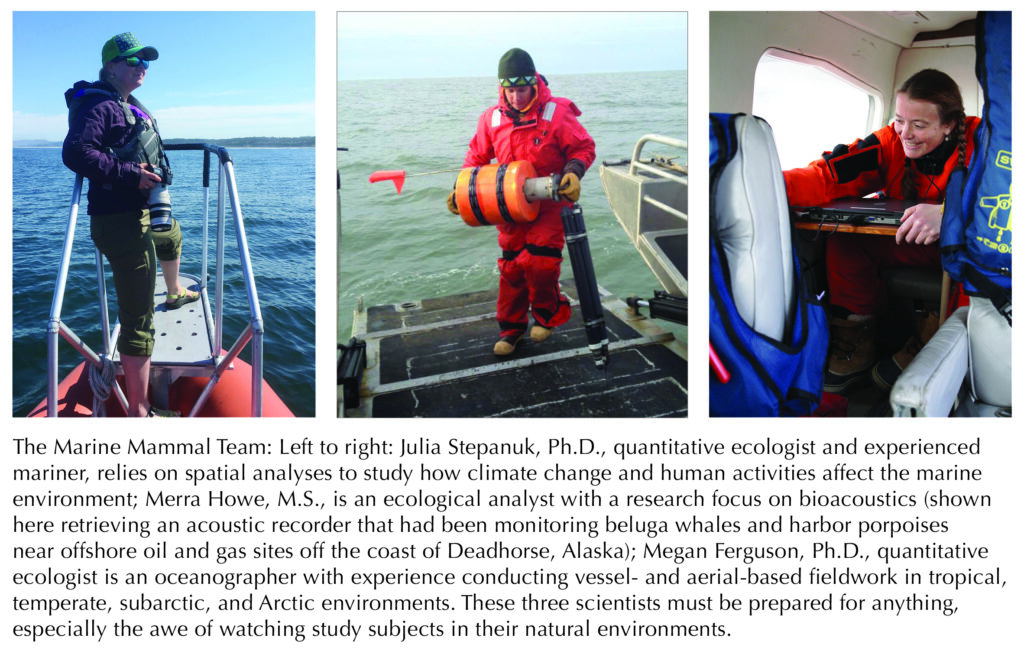

Julia controls a drone flying over open ocean. Once she spots a whale, she sends the drone 100-120 feet high and aims for the perfect shot. All work was conducted in compliance with federal research permits

Julia Stepanuk, Ph.D., Quantitative Ecologist

Julia is no stranger to the ocean. At only 14 years old, she volunteered for Allied Whale and the Bar Harbor Whale Watch Company. Rising through the ranks of the Company over the years, she began guiding whale watching trips and collecting data from the boat as a scientist.

Leading up to graduate school, Julia spent months at sea learning the ropes (literally) of operating a 134-foot Tall Ship operated by Sea Education Association, sailing from Hawaii to Tahiti and San Diego to Nuku Hiva of the Marquesas Islands.

During her voyages, Julia collected and analyzed data that would contribute to long-standing oceanographic datasets collected by the organization. These trips through the Pacific Ocean and along the coasts of Maine, New York, and Antarctica taught her the leadership and teamwork skills she would use throughout her career.

Julia’s talents are not limited to the ocean, however. To be an excellent scientist, you have to not only become an expert in your chosen field, but you must also master complementary skills that help you stand out from the crowd. Luckily for Julia, mathematics and coding come naturally. She can transform spreadsheets of data into models that can answer complex questions about whale populations that are meaningful to wildlife managers from state and federal organizations. One of Julia’s methods of data collection involves using drone imagery. Working out of Long Island, New York, Julia has spent many hours operating a drone from a boat, learning how to position it over a humpback whale to get the perfect shot, tip to tail.

Using this method, she has collected images of 75 individuals over 5 years. These images were used to determine the health of the humpback whale population in the New York Bight region. Health was evaluated by using body size characteristics—sort of like a body mass index (BMI) for people. “Their size reflects how important whales are to the ecosystems in which they live,” Julia explains. She was even able to forecast whales like the weather, using models that can predict when and how many humpback whales will be off the coast of Long Island. This is important because whales often come in close contact with fishing vessels and recreational watercraft, near and far from shore. Knowing how many whales are out there and when helps to prevent collisions, saving lives and preventing serious injury.

Through her research, Julia has measured humpback whales whose sizes ranged from 30 to 50 feet in length. After all her years of studying these gentle giants, it’s still not lost on Julia just how impressive their size is. When asked what she wishes people understood about whales, she responded simply, “It’s just so cool how big they are!” Her answer was gleeful. Surely imagining the many close encounters she has experienced throughout her career, it’s that kind of enthusiasm that fuels the dedication to her work at BRI.

What excites Julia most about the Marine Mammal Program is that she can focus on preventing negative impacts to whales before they have a chance to happen. Noise pollution from vessel traffic, vessel strikes, and fishing gear entanglement are some of the many threats Julia hopes to address. To add to her challenges, the effects of climate change present a slew of unexpected problems that could amplify existing threats. Locally and globally, there is a wealth of information about marine mammals, but there is still so much to learn about their presence in the Gulf of Maine. Through field surveys, statistical modeling, and collaboration with other agencies, universities, and conservation groups, Julia is on a quest to make those discoveries.

Megan prepares to board a twin-engine Turbo Commander in Utqiaġvik (pronounced oot-kay-ahg-vik), Alaska to conduct surveys. If conditions are optimal, her crew can make two survey flights in a 12-14 hour day, which includes time flying, refueling, data collection, and a survey report.

Megan Ferguson, Ph.D., Quantitative Ecologist

Hailing from Salt Lake City, Utah, Megan didn’t grow up in an environment that would naturally foster an interest in marine biology. Luckily for BRI, Megan spent her summers on the California coast where she fell in love with the ocean. Watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries with her family also ignited her burgeoning passion.

When it came time to think about college, it was no surprise that she chose the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences in Seattle. Her first formative experience was during her internship with the Marine Mammal Laboratory at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, where she was immersed in work at the intersection of applied ecology, mathematics, and wildlife management. This interdisciplinary field of studying marine mammals was where Megan felt most inspired. From there, Megan’s career led her to the prestigious Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, where she studied biological oceanography.

A natural problem solver, Megan wanted to answer the question: How do all of the pieces (biology, physical oceanography, geography, human activities) interact to shape and transform ecosystems?

To find out, she spent weeks on research vessels in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean performing visual and acoustic sampling of whales and dolphins, and collecting physical and biological oceanographic samples. Her most profound experience though, came in an entirely different environment: the Alaskan Arctic.

From the vantage point of an airplane, Megan set out to estimate sizes of whale populations vital to Indigenous peoples in Alaska. Through collaboration with Native subsistence hunters, scientists, and wildlife managers, she worked with the Alaska Beluga Whale Committee and Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission to conserve and manage belugas and bowhead whales using a combination of Indigenous knowledge and western science. On a larger scale, she developed methods to delineate marine areas that are important to cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) for feeding, migration, and reproduction.

The Pacific Arctic is in transition. Common cetacean species in this region are bowhead, beluga, and gray whales. However, during Megan’s time collecting data in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, she noticed an uptick in sub-Arctic species including fin, minke, and humpback whales. Like many species on land, some marine mammals are shifting their ranges north due to climate change. In addition, with fewer days of ice obstructing the Bering Strait (also called the Northwest Passage), there is a longer season during which vessel traffic can pass between the Chukchi and Bering seas. With more vessels comes more noise, which is disruptive to whale communication and increases the risk of collision and accidental release of pollutants and debris.

Megan is always looking for solutions to complex ecological issues. Through the Marine Mammal Program, she looks forward to continuing her work collaborating with Indigenous communities; local, state, and federal organizations; nonprofits; developers; universities; and fishermen. Working alongside Julia, these pioneering scientists intend to use the best available information in the best way possible to achieve conservation and management goals for marine mammals. Their combined backgrounds will enable them to tackle many of the present and future challenges to marine mammals.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Program.

![]()

Maine Perspectives on Climate Change

By Caitlin Guthrie, USM Communications Intern

Roots are exposed by coastal erosion in Southern Maine. Photo by Caitlin Guthrie.

The sun shines on the cold, deep blue ocean at Fort Williams Park in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Portland Head Light, an iconic landmark that draws in three million visitors each year, stands proudly at the edge of the rocky shore. The view of Maine’s southern coast from here is perfect. However, there is a big problem shrouded within this picturesque landscape.

Peering over the edge of a nearby bluff, you can see that the water is slowly eroding it. Live roots can be seen in the dirt along the face of the bluff, appearing ripped apart by the ocean. Erosion like this happens when the water levels reach record highs relentlessly pounding the coast, which has already happened several times this year in Maine.

According to National Geographic, rising sea levels increase the intensity of storm surges and flooding in coastal areas, leading to increased storm damage. Storms are wreaking havoc on Maine’s iconic coastline and it’s getting worse with every storm.

Historic fishing shacks in South Portland are destroyed by a severe storm. (Photo by Susan Young/The Bangor Daily News via AP)

During a severe storm in January, South Portland said goodbye to its historic fishing shacks that have stood at Willard Beach since the 1800s. The shacks were washed away during the storm when water levels hit over 14 feet, according to USA Today and the National Weather Service. Treasured and adored by the community, the fishing shacks represented a proud heritage of life by the sea. They were often used as backdrops for important moments such as graduation photos and marriage proposals. And now, these pieces of history are gone. The story was even picked up by the New York Times.

Along with the rising sea levels and intense storm surges, the water is also getting warmer. Devan Newell, 21, has been witnessing the harsh effects of warming waters in Maine for many years. When Devan was ten, he started to notice an alarming number of seals washing up on the beach in his neighborhood. The warming of the Gulf of Maine has caused acidity levels to rise in the ocean, making seals more prone to fatal infections.

According to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than practically any other ocean surface on the planet due to the strengthening of the Gulf Stream which is bringing in warmer water. U.S. News claims that 70 percent of American marine mammal species are vulnerable to threats like loss of food and habitat due to warming waters.

Seeing dead seals on the beach upset young Devan and inspired him to take action to help the seals. To raise money, Devan and his neighbor started painting rocks they found on the beach and sold them around town. They raised thousands of dollars for Marine Mammals of Maine, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the health and safety of all marine mammals and sea turtles in southern and midcoastal Maine. “It felt really good to raise that money. Even though it was a long time ago, I know that my donation made a positive impact,” says Devan.

According to the Ocean Conservatory, the ocean has absorbed over 90 percent of heat from human-caused industrial waste, especially carbon emissions. While the ocean has protected us from the worst effects of climate change since the beginning of industrialization, we can no longer deny the harmful effects the ocean has endured due to the accumulated effects of all this

pollution.

Brian Guthrie, 61, a long-time resident of southern Maine, has noticed a big change in how warm the water is getting. “It smells sweeter, too, because the water is becoming more tropical with global warming.”

With all the information in the news and the visible changes in our environment, it can be hard to keep an optimistic outlook on the future of our planet. Especially with access to social media, everyone has a magnifying glass on current world issues. You could be halfway across the globe and still stay up to date on current events, including the impacts of climate change in certain areas. Even though the media bombards us with negative information about climate change, it is important to stay optimistic and get involved. There is so much you can do to help make meaningful change, “one drop of water” at a time. As Devan did, get creative and get involved!

Getting involved will help inspire optimism. Here are a few examples of how you can be one

drop of water:

- Volunteer with organizations such these:

–Biodiversity Research Institute

–Gulf of Maine Research Institute

–Marine Mammals of Maine

–ClimateWork Maine - Donate to any one of hundreds of nonprofits promoting public awareness of these issues

- Vote for environmentally responsible local politicians.

- Watch An Optimists Guide to the Planet, a new six-episode television series that focuses

on solutions to some of the biggest environmental challenges of our time.

![]()

No Stop Signs at the Intersection of Science and Policy

No Stop Signs at the Intersection of Science and Policy

By Deborah McKew, BRI Communications Director

Mercury studies in Indonesia. Climate change studies in Tanzania. Biodiversity studies in South Dakota. Marine mammal surveys in the Atlantic Ocean. BRI’s conservation biologists are literally all over the map. Over the course of 25 years, a small group of wildlife researchers monitoring mercury in loons and eagles in Maine grew into a global organization that works at the highest levels of international environmental research. With that advantage comes the responsibility of informing and helping shape the contours of policy—a responsibility BRI founder and chief scientist David Evers takes very seriously.

Mercury studies in Indonesia. Climate change studies in Tanzania. Biodiversity studies in South Dakota. Marine mammal surveys in the Atlantic Ocean. BRI’s conservation biologists are literally all over the map. Over the course of 25 years, a small group of wildlife researchers monitoring mercury in loons and eagles in Maine grew into a global organization that works at the highest levels of international environmental research. With that advantage comes the responsibility of informing and helping shape the contours of policy—a responsibility BRI founder and chief scientist David Evers takes very seriously.

BRI is an organization of scientists whose research aims to answer questions critical for maintaining a healthy earth: How do ecosystems work? How do contaminants affect those ecosystems? How do wildlife respond to environmental stressors over time? But an additional role that BRI embraces is to provide a service to policymakers. “As a scientist, you want to understand and learn for the sake of learning, for the sake of knowledge,” says Evers. “But the power is in bringing that knowledge to the people who can use it.”

The foundation for this journey began with BRI’s mission, which placed innovative wildlife research and scientific integrity on an equal footing with sharing knowledge gained from this research with those who make policy decisions. Building upon early successes in its research collaborations, BRI has cultivated the expertise and resources needed to develop innovative study designs, achieve more precise analysis, and maintain objective and informative interpretation.

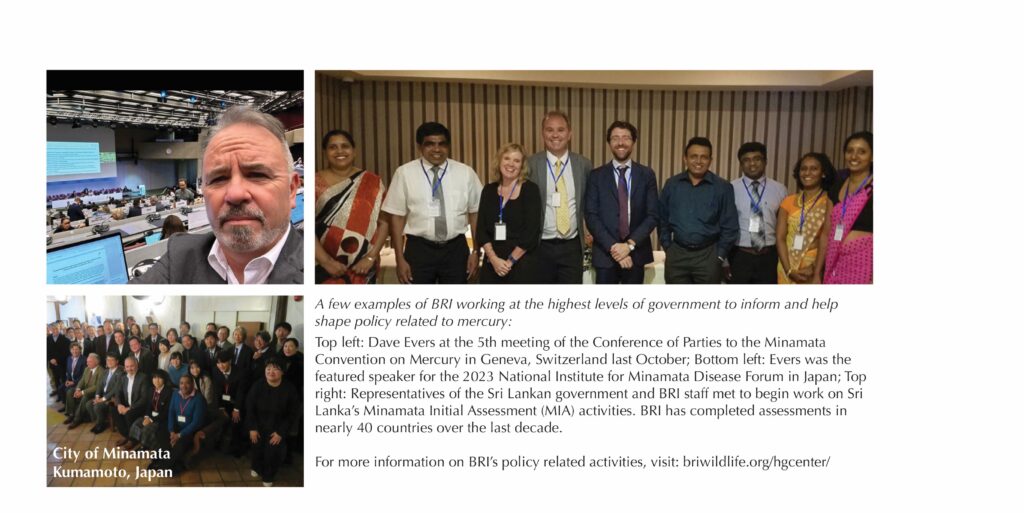

A pivotal moment for BRI came in 2011 when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency invited Evers, renowned in his field of mercury studies, to join the scientific committee for the United Nation’s first global agreement designed to address contamination from a heavy metal—the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Evers understood the importance of providing critical scientific data to the international delegates responsible for crafting this policy, but he saw BRI’s research stretching far beyond the ratification of the treaty.

Tracking Mercury on a Global Scale

The Minamata Convention was put into force in October of 2017. An important provision of the Convention is to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the adopted measures and its implementation—no small feat given the complexities of how mercury moves through air, water, and land.

With years of published mercury data on wildlife in North America compiled into a single database, BRI was poised to take the lead in developing methods for collecting mercury data and monitoring changes over time on a global scale—exactly what the Convention needed. Known as the Global Biotic Mercury Synthesis (GBMS), this database now includes more than 550,000 data points detailing each organism sampled, its sampling location, and its ecological profile. That information is used to understand patterns of mercury concentrations in wildlife across time and space, helpful in identifying species and ecosystems most at risk. Mapping risk helps improve efforts to reduce the impact of mercury pollution on people and the environment.

In addition to the GBMS database, which contains only peer-reviewed published data, the Secretariat of the Minamata Convention has initiated an Open-ended Science Group (OESG) to help monitor mercury reduction in each country that has ratified and is a Party to the Convention. Made up of one representative from each Party, this group will contribute countrywide data, both published and unpublished, pertaining to mercury monitoring in air, water, wildlife, and people. BRI is the lead organizer for this group and is developing protocols to standardize and harmonize data originating from various sources so that the information is presented in a clear and accessible format.

Building on Commitment, Collaboration, and Communication

As BRI has grown, the organization has made it a priority to develop a standard of science communications that provide nonscientists clear information—facts about a specific problem, such as mercury contamination—and how BRI is gathering, analyzing, and interpreting those facts. To further enhance global collaboration and communication, BRI is building a staff of highly skilled scientists who also have experience working in different sectors, including policy and industry.

It’s not an understatement to say that there are huge environmental issues facing our world today. On the horizon, BRI has projects that aim to reduce the triple threat of climate change, loss of biodiversity, and ongoing contamination of our natural resources. “To me, it’s all about building blocks, building off of past successes and platforms that were generated and developed,” says Evers. “And then working to build those blocks up to something higher, working toward more elevated goals.”

The Minamata Convention is one of those building blocks for BRI, which has led us to collaborate with other Conventions including the Convention for Biological Diversity and the Framework Convention on Climate Change. “Our niche is as detectives for the environment. Whether we are working in Maine or in Tanzania, wildlife need a voice. BRI is one such voice.”

![]()

Photo Credits: Header photo © BRI

The Ocean Alliance

The Ocean Alliance