Harlequin Ducks in Wyoming: A species of greatest conservation need

By Eleanor Eckel, Science Policy Coordinator

arlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) are a small, brightly colored duck species known for their striking plumage and the dramatic landscapes where they live and breed. The blue, chestnut, and white males, along with the grayish females, breed in subalpine or coastal habitats, including the northern boreal regions of eastern Canada, the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and Canada, Alaska, and the Rocky Mountain regions. The breeding habitat requirements of the Harlequin Duck consist of clear, rapidly flowing streams and rivers that support macro-invertebrates. These unique ducks forage by diving for invertebrates and insect larvae attached to streambed rocks in turbulent waters. Photo by Ryan Askren.

arlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) are a small, brightly colored duck species known for their striking plumage and the dramatic landscapes where they live and breed. The blue, chestnut, and white males, along with the grayish females, breed in subalpine or coastal habitats, including the northern boreal regions of eastern Canada, the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and Canada, Alaska, and the Rocky Mountain regions. The breeding habitat requirements of the Harlequin Duck consist of clear, rapidly flowing streams and rivers that support macro-invertebrates. These unique ducks forage by diving for invertebrates and insect larvae attached to streambed rocks in turbulent waters. Photo by Ryan Askren.

The Harlequin Duck is one of the rarest breeding birds in the state of Wyoming. They breed exclusively among mountain streams in the northwestern portion of the state, with significant concentrations in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. The ducks breed in the western U.S. and Canada and migrate to the Pacific coastline for the winter. However, the specific migration routes, timing, and habitat types used during post-breeding activities (i.e., molting, staging, and migration) are much less understood for most western U.S. breeding harlequins. To conserve Wyoming’s Harlequin Duck population, the species’ year-round habitat requirements, general breeding ecology, and migration patterns must be better understood.

To address these knowledge gaps, BRI researchers conducted a Harlequin Duck migration study in Wyoming during 2016-2018. In spring of those three years, wildlife biologists and veterinarians from the U.S. and Canada spent time in the field, at harlequin breeding streams, to capture pairs and attach tracking technology to track the migrations and seasonal movements of breeding Harlequin Ducks. The male harlequins were equipped with a specialized implantable satellite transmitter, while a small geolocator tracking device was attached the to the leg bands of the females. In addition to Wyoming, collaborators tagged pairs of breeding Harlequin Ducks in Montana, Washington, and Alberta, Canada. Satellite telemetry is a commonly used and effective technique utilized to track annual movements of birds, and the data can be used to identify the specific locations and timing of important molting, migration, and wintering sites—necessary data to conserving the harlequin duck population.

To address these knowledge gaps, BRI researchers conducted a Harlequin Duck migration study in Wyoming during 2016-2018. In spring of those three years, wildlife biologists and veterinarians from the U.S. and Canada spent time in the field, at harlequin breeding streams, to capture pairs and attach tracking technology to track the migrations and seasonal movements of breeding Harlequin Ducks. The male harlequins were equipped with a specialized implantable satellite transmitter, while a small geolocator tracking device was attached the to the leg bands of the females. In addition to Wyoming, collaborators tagged pairs of breeding Harlequin Ducks in Montana, Washington, and Alberta, Canada. Satellite telemetry is a commonly used and effective technique utilized to track annual movements of birds, and the data can be used to identify the specific locations and timing of important molting, migration, and wintering sites—necessary data to conserving the harlequin duck population.

Science informs conservation

BRI biologists also completed ground surveys that consisted of two individuals who walked and waded stream stretches with known, suspected, or historic breeding records. Researchers used GPS technology to document their surveys, and binoculars for visual observations. They chose their observation locations and timed their surveys based on the earliest known observation periods to arrive before the spring tourist season. While surveying, researchers documented the age and sexes of individuals and checked for leg bands to identify birds returning from previous capture efforts.

BRI biologists have also begun testing a novel method of detecting Harlequin Ducks on remote breeding streams in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. By pumping stream water through a small paper filter, biologists can collect a sample that can later be analyzed at the lab for the presence of harlequin DNA fragments left in the environment. This method of sampling environmental DNA (eDNA) may allow researchers to better assess the breeding population in Wyoming and determine its presence in remote wilderness areas that are difficult to access and survey on foot.

This year, biologists are conducting a combination of ground surveys, eDNA surveys, and game camera deployments to determine which creeks/drainages in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are occupied by Harlequin Duck pairs. This summer’s work will help to: identify streams with resident breeding pairs, helping to home in on areas that are worthy of more extensive surveys, such as brood surveys, later in the summer; and to identify areas to target for future capture efforts. The ideal next step in the study will be to deploy small GPS units on hens to identify fine-scale nesting habitat selection and brooding locations. At this point, the study has no end date, however with additional funding the team hopes to build this work into a larger scale multi-year effort.

For more information and updates on this project, visit: https://briwildlife.org/harlequins/

Link: Report

________________________________________________________________________________________________

For the Love of Ducks

By Deborah McKew, BRI Communications Director

It’s 3:07 in the morning on the last day of scoter capture. Dustin Meattey wakes to a dismal weather forecast: 25 mph winds, rain, and sleet. Less than 15 minutes later, the intrepid biologist joins his fellow crewmates at the launch site where they don winter rain gear, load their motorboat with nets and decoys, check equipment, slip the boat into the water, and drive through the darkness. On board, activity continues as the crew tie decoys to the wide mist nets, which they will anchor in the coastal waters off Revere Beach in northern Massachusetts. The wind and rain haven’t kicked up yet, but they know it will. Photo, BRI Staff.

Racing against the coming storm, this experienced crew work in a choreographed method to install nets and position decoys. They then wait undetected for the scoters to fly in for some breakfast. The sound of flapping wings in the early dawn put the biologists on alert: the scoters have sighted other ducks (decoys) gathering to feed, but the nets block their way. The crew spring into action to untangle birds caught in the nets—each bird processed for tagging in just minutes, then released back to the water unharmed.

Capturing sea ducks for study is not for the faint hearted, but Dustin lives for it. He credits his love of nature and adventure to his uncle, who visited his family once a year around the holidays. “He would always take my sister and I, from the time we could walk, out tromping through the woods in the winter, belly crawling across frozen ponds that weren’t quite frozen enough, camping out, exploring. Whenever he came to our house, I knew there would be some kind of woodsy excursion,” remembers Dustin.

Dustin’s adventurous spirit serves him well in his current position as the director of BRI’s Waterfowl Program. His professional journey started in the summer of 2004, when he, newly graduated from high school, volunteered for the Loon Preservation Committee (LPC) in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire, his home state. At that time, the world of loon researchers was very small. Kate Taylor, a biologist at LPC, was Dustin’s supervisor. Admiring him for his innate abilities in the field, she mentored him in “all things loon.” When Kate left LPC to help build BRI, she persuaded Dustin to come along and his continued tenure (through college and graduate study) at BRI began.

From the beginning, Dustin was willing and able to handle any assignment that came his way—from loons, to raptors, to bats, to sea birds, and more. He was nicknamed BRI’s “utility knife” biologist. Whenever one of the wildlife programs needs some extra hands for a project, they call on Dustin. Experience working with almost every taxonomic group helped him hone his skills, but more importantly, the variety of species helped him recognize his true passion and interest in waterfowl studies.

Dustin embodies the philosophy of BRI’s culture. His research is not a job to him, but a deliberate way of life. Dustin and his colleagues are hardy souls who endure long hours in all manner of weather and conditions. In the field, “you are always so focused on troubleshooting the issues that come up, dealing with changing conditions, trying to make the best of a crappy day and still get the job done.”

Dustin embraces the challenges of working in the marine environment. He enjoys “the physicality of the work, the exhilaration of it, the element of danger sometimes . . . that piece of it first drew me in. Then a real appreciation and love for waterfowl ecology and conservation built off the fact that this is just really fun work to do, and I want to do it all the time.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

From Spark to Action

By Alyssa Soucy and Allison Foster, University of Maine Graduate Students

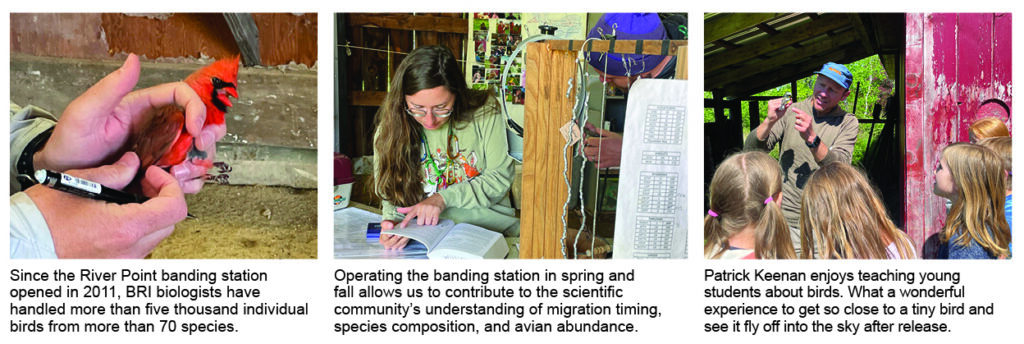

long the gravel meadowed trail at River Point Bird Observatory, a passerby stops to get a closer look at the murmuration of starlings circling in the distance through his binoculars. Ed Jenkins, avian ecologist at BRI, begins to chat with the birder about recent sightings at the banding station. Between documenting the thousands of birds that migrate through the observatory, Ed dedicates time to outreach and informal education by engaging with visitors. Ed says, “It just takes a very short discussion with a passerby for them to be interested about why this little piece of land where they live is important and exciting!”

Using songbirds to capture the imagination, Ed authentically shares the mission of BRI with others. “I see it all the time when a family with a young child comes to River Point and I can show them a live bird in the hand, you can just see this spark of “wow this is great, I’d never thought I’d see this so close up.” Once that spark is ignited, the possibilities for connection are endless.

In a past issue of One Drop of Water, we discussed the importance of human connection to nature for long-term sustainability. As the gap between humans and nature widens, education can act as a bridge to raise awareness and foster environmental literacy.

A growing body of research supports the key role of education in building local capacity for conservation. When people can genuinely engage with environmental management and conservation efforts, their awareness, knowledge, and values can shift towards sustainable behaviors. We live in a world with increasingly complex conservation challenges. Humans have a great impact, both positive and negative, on wildlife species.

BRI staff are committed to translating science to be accessible to the public, which in turn spurs action. Tim Tear, Director of the Center for Climate Change and Conservation, says that certain conservation challenges can often lack impact for a wide audience. Tim notes, “Best to share things that people relate to everyday life,” he adds, “That’s what makes it real.”

On River Point’s Instagram, Ed reaches an even wider audience as the birds take center stage in his photographs. His photographs have led to increased interest in the work of BRI, for example, attracting volunteers who apply to help at the banding station after seeing the social media account. Education catalyzes long-term conservation action—whether that involves pursuing a career in environmental sciences, supporting management efforts for biodiversity management efforts, voting to elect politicians who support climate change policy, or donating one’s money or time.

Founded in 2011, River Point hosts 15-20 school groups throughout the year. Around mid-morning, a local school group arrives eager to see what is happening. Patrick Keenan, one of the key biologists who created the banding station, sits down with students and talks about some of the birds that are seen here, showing them a yellow-throated warbler. When engaging with the students, Patrick compares the number of birds at River Point to the students in the class, and the kids continue to crowd around Patrick, their interest only growing. The students interject the conversation with their comments of “birds are special” and “birds are smart”—evidence of their newfound awareness. At the end of their visit, the students share which bird is their favorite. It’s inspiring to hear how each student has an individual connection to “their” bird and the world around them.

At BRI, education not only occurs via one-on-one interactions, school groups, or social media, but also as part of a larger effort to engage people in conservation using art and stories. It is through the conversations that BRI scientists have with the public out in the field, the imagery on social media, and their scientific communication efforts that tell the stories behind BRI’s research that we can make science relatable and real. As visitors to River Point Observatory go for a walk on their local nature trails, a magical moment of connection can have lasting impacts on our abilities to collectively address conservation challenges.

Side by side with outreach, BRI avian biologists have continually worked to build the largest banding data set in Maine. As part of this work, BRI collaborates with other organizations on research projects such as sampling project with Maine Medical Center Vector-borne Disease Lab for monitoring ticks on birds. Science conservation can happen through these types of research projects but also through local outreach so we can understand our relationship with the environment. River Point is a prime example of this outreach in action.

River Point Bird Observatory is a part of River Point Conservation Area in Falmouth, Maine, and is open to the public year-round. If you’re ever interested in birding and seeing how conservation happens close to you, spend a morning at River Point!

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Changing Policy and Perceptions: Eliminating mercury skin lightening products

By Deborah McKew, BRI Communications Director

In his seminal work Meteorology, Aristotle coined the term “quicksilver” to describe mercury. Since antiquity, humans have exploited this liquid metal for its unique characteristics—it is a good conductor of electricity, forms alloys with other metals, is sensitive to heat and pressure, and acts as a preservative. One of the seven metals of antiquity,* mercury has historically been used in many consumer and industrial products. Photo by Tahlia Ali Shah.

Mercury in Skin Lightening Creams

Mercury is a common ingredient used in skin lightening or anti-aging soaps and creams because mercury salts inhibit the formation of melanin, the pigment that gives human skin, hair, and eyes their color. Using cosmetics to inhibit the body’s production of melanin, which causes the skin to appear lighter, is a centuries-old practice in many parts of the world.

Both men and women use skin lightening products, not only to lighten their skin but to fade freckles, blemishes, age spots, and to treat acne. However, consumers are often unaware that many of these products contain mercury, which poses risks to human health and contaminates the environment.

Regulations on Mercury in Cosmetics

The U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA) banned mercury in most cosmetics in 1974. The FDA has set a maximum allowable limit for mercury in cosmetic products in trace amounts only (generally no more than one part per million). The distribution of mercury-added creams and soaps is banned in the European Union (EU) and in some African countries. However, many other countries are not bound by these standards and may still include mercury as an ingredient in these skin care products, which can be easily obtained online.

Risks to Human Health and the Environment

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the main health risk to those who use skin lightening products that contain mercury is kidney damage, but the use of these products can also result in skin rashes and discoloration; scarring; nervous, digestive, and immune system damage, as well as anxiety and depression.

In addition to human health, the environment is also at risk. Mercury in these products is eventually released into wastewater where this toxin enters the environment and, under certain conditions, can be converted to methylmercury (the organic form of mercury), which then can be absorbed into the food web, contaminating the food we eat.

The Minamata Convention on Mercury has set a limit of 1mg/1kg (1part per million) for mercury in skin lightening products. However, in 2018 Biodiversity Research Institute, in collaboration with the Zero Mercury Working Group, tested more than 300 products from 22 countries and found that approximately 10 percent of skin lightening creams exceeded this limit, with many containing as much as 100 times the authorized amount.

A Global Issue

Mercury’s use in consumer products has amplified its recognition as a pollutant of global concern. The Minamata Convention on Mercury seeks to address “the harmful effects of mercury pollution” by drawing worldwide attention to the effects of exposure and widespread use of mercury found in everyday products. Under the Minamata Convention, which entered into force 2017, individual countries that become Parties to the Convention are charged with protecting human health and the environment from the risks of mercury exposure.

Three of these countries are now part of a global initiative to reduce mercury in cosmetics. The governments of Gabon, Jamaica, and Sri Lanka have joined forces to fight back against damaging beauty practices, launching a joint $14-million project to eliminate the use of mercury in skin lightening products.

Led by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), with funding from the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and executed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Biodiversity Research Institute (BRI), the Eliminating mercury skin lightening products project will work to reduce the risk of exposure to mercury-added skin lightening products, raising awareness of the health risks associated with their use, developing model regulations to reduce their circulation, and halting production, trade and distribution across domestic and international markets.

“Mercury is a hidden and toxic ingredient in the skin lightening creams that many people are using daily, often without an understanding of just how dangerous this is,” GEF CEO and Chairperson Carlos Manuel Rodriguez said. “This initiative is significant as it focuses not only on substitutions for harmful ingredients, but on awareness building that can help change behaviors that are damaging to individual health as well as to the planet.”

With demand for skin lightening products projected to grow to $11.8-billion by 2026, fueled by a growing middle class in the Asia-Pacific region and changing demographics in Africa and the Caribbean, the use of harmful ingredients in skin lightening products is a global issue.

“WHO calls for urgent action on mercury as one of the top chemicals of public health concern. The health impacts of mercury have been known for centuries but more people should become aware now,” said Dr Annette Prüss, Acting Director, WHO Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health.

The three-year project will bring the countries together to align their policies on the cosmetic sector with best practice, creating an enabling environment to phase out mercury and attempting to shift broader cultural norms on skin complexion through engaging organizations, healthcare professionals and influencers working in the field.

BRI’s Contribution to the Project

In the first year of this three-year project, BRI scientists will conduct the field studies in each of the countries to collect skin lightening products, analyze them for their mercury content, generate a global database, and provide interpretation for those data. The goal is to bring the three participating countries together to align their policies on the cosmetic sector with best practice, creating an enabling environment to phase out mercury and attempting to shift broader cultural norms on skin complexion through engaging organizations, healthcare professionals and influencers working in the field.

As experts in the field of mercury science, BRI researchers were invited by U.S. government officials to participate as a nongovernmental organization (NGO) during the negotiating process of the Convention. BRI now serves as co-lead of UNEP’S Mercury Air Transport and Fate Research partnership area. As a co-lead, BRI assists with development of a globally coordinated mercury monitoring and observation system.

“For more than a decade, we have been working to help facilitate the goals of the Minamata Convention,” says David Evers, BRI’s executive director and chief scientist. BRI now serves as an Executing Agency for the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and UNEP and as an International Technical Expert for both UNEP and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). “This cosmetics project exemplifies how important it is for science to inform policy. We are proud to be part of such a prestigious team of collaborators.”