Seven thousand miles from Portland, Maine

By Deborah McKew, BRI Communications Director

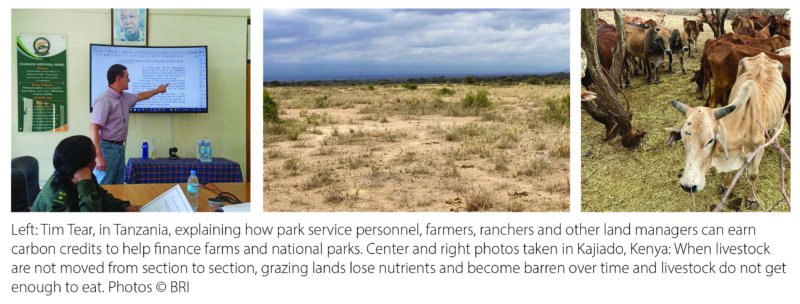

In a sparsely furnished office in Kajiado, Kenya, large sheets of white paper cover nearly an entire wall. Quick illustrations, mind maps, color-coded charts, and task lists cram the pages with plans and strategies for grazing management orchestrated by the newly formed Kajiado Rangeland Carbon Project team. In the language of the local Maasai tribe, Kajiado means The Long River; the region is located south of Nairobi and bordering Tanzania. Staff on this project understand what is at stake and are eager to embark on an adventure that will help enhance their local economy while conserving wildlife and precious habitat.

In a sparsely furnished office in Kajiado, Kenya, large sheets of white paper cover nearly an entire wall. Quick illustrations, mind maps, color-coded charts, and task lists cram the pages with plans and strategies for grazing management orchestrated by the newly formed Kajiado Rangeland Carbon Project team. In the language of the local Maasai tribe, Kajiado means The Long River; the region is located south of Nairobi and bordering Tanzania. Staff on this project understand what is at stake and are eager to embark on an adventure that will help enhance their local economy while conserving wildlife and precious habitat.

In early 2022, BRI partnered with CarbonSolve and others to develop carbon projects in grassland and rangeland habitats where grazing and/or fire management are the dominant activities. The group has recently launched a 1.5-million-hectare soil carbon project in the Kajiado District of Kenya’s southern rangelands region.

“This is a new area of research and development in carbon projects,” says Tim Tear, Ph.D., director of BRI’s Center for Conservation and Climate Change. “Our focus is specifically on improving carbon in the soil. We are implementing knowledge gained from our research to on-the-ground projects, working with pastoralists in sub-Saharan Africa on rotational grazing of livestock, as well as on fire management in national parks and protected areas in Africa to generate carbon revenues that allow you to move these projects forward in the long run.”

Why Soil Carbon and Why Now?

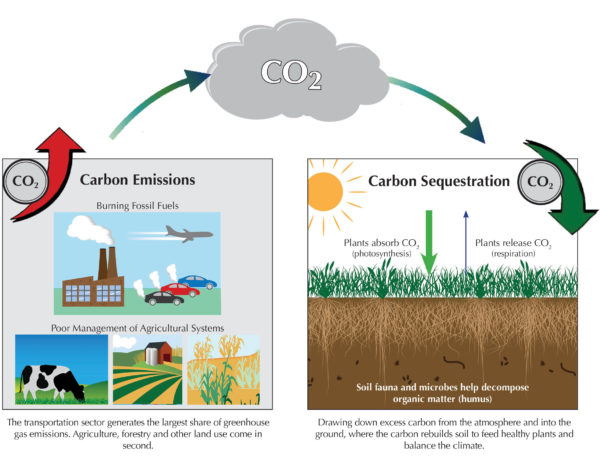

The global imperative to address climate change continues to increase along with interest in carbon offsets, as public and private entities strive to achieve NetZero targets. The value of carbon credits is increasing as demand outstrips supply, and investors are increasingly interested in carbon sequestration and avoided emissions. Combining both sequestration and avoided emissions increases land management value.

“Talking about carbon and the carbon markets can be abstract and complicated, and a lot of these concepts get lost on most people,” says Tim. “But when working with people in pastoral communities who understand rotational grazing with livestock, or fire management personnel in a national park system, where these activities are already under way, they clearly see the potential benefits of these climate projects. The ability to reach consensus and understanding is quite quick and it’s extremely exciting when you see that happen.”

“Talking about carbon and the carbon markets can be abstract and complicated, and a lot of these concepts get lost on most people,” says Tim. “But when working with people in pastoral communities who understand rotational grazing with livestock, or fire management personnel in a national park system, where these activities are already under way, they clearly see the potential benefits of these climate projects. The ability to reach consensus and understanding is quite quick and it’s extremely exciting when you see that happen.”

BRI’s special expertise of long-term monitoring wildlife movements and their responses to development activities, conducting long-term studies on contaminants in the environment, and applying scientific knowledge gained leads to a better understanding of the stressors impacting wildlife populations and insight on how best to provide solutions to those issues.

“BRI’s climate change studies matter because there are very tangible steps that we’re taking that will make a difference,” says Tim. “Everyone needs to find the tangible steps that they can take—it all adds up to big changes.”

What influences the amount of carbon in the soil?

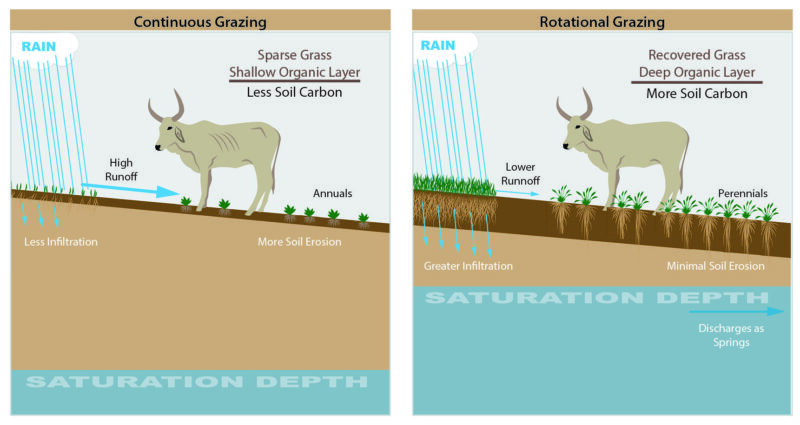

Rotational grazing utilizes a portion of the grazing land while allowing the remainder to “rest.” Livestock is rotated from section to section, which leads to recovered grass, greater infiltration with lower runoff, and a deeper organic layer of soil that absorbs more carbon. More soil carbon means greater moisture retention and nutrient cycling capacity, making the land more resilient to drought.

Fire management is also an important aspect of land management. Land managers can accomplish a “cooler” burn by intentionally starting grassland fires early in the dry season, using less woody fuel overall but still removing enough vegetation to prevent unintended high-intensity fires later in the season. As a result, less carbon emissions are released into the atmosphere, while more carbon is retained in the soil.

Both outcomes are quantifiable and sellable as carbon offset credits on the global carbon market.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Evan Adams – Champion of Songbirds

By Alyssa Soucy, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Maine

“Gray catbird. Second year. Molt limit present. Unknown sex. Wing 87. Weight 35.”

“Gray catbird. Second year. Molt limit present. Unknown sex. Wing 87. Weight 35.”

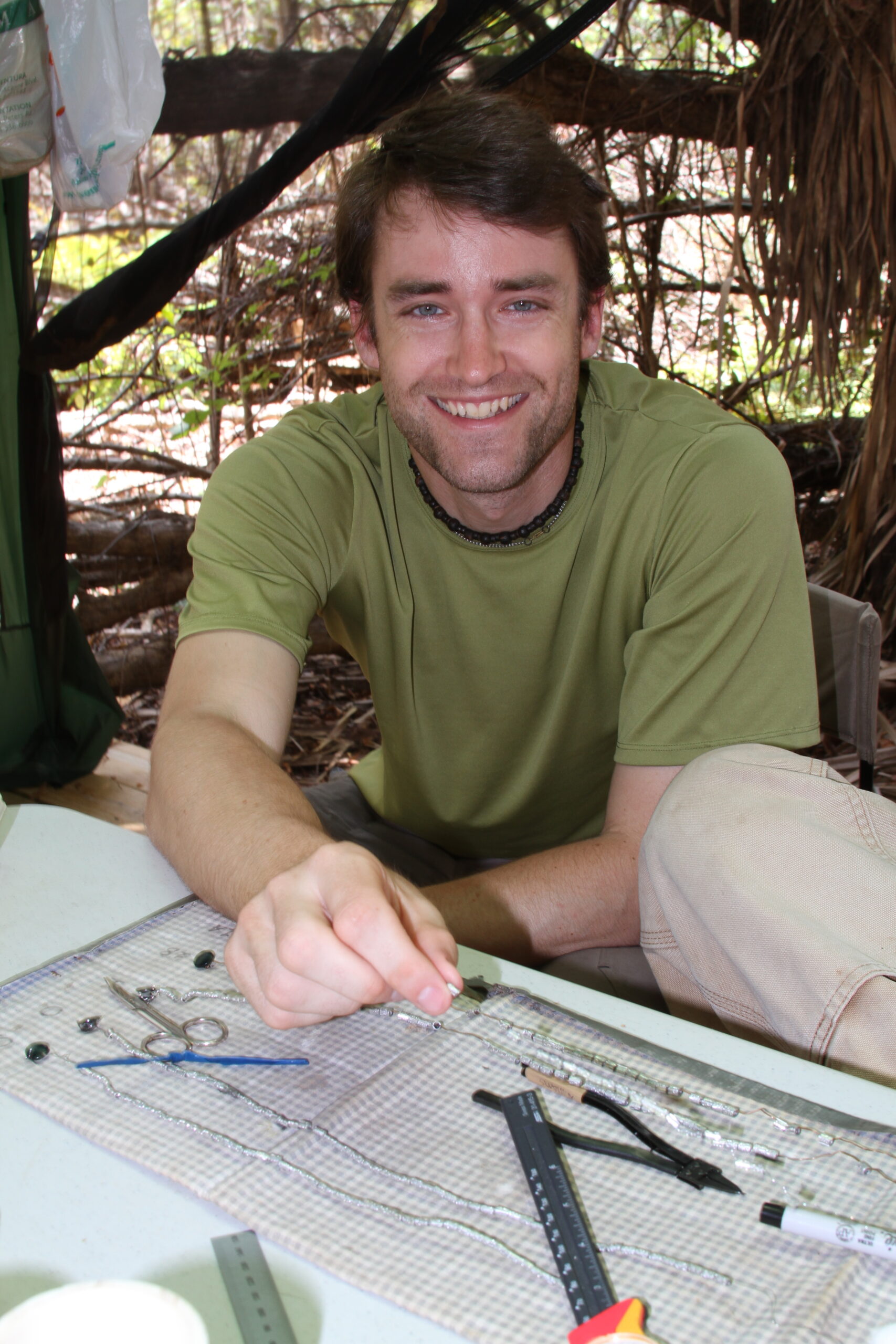

Evan Adams is in his sixth and final hour of identifying and banding birds at BRI’s River Point Bird Observatory. Inside the red barn, he stands next to a workbench, on which sits a pair of binoculars and a worn copy of the book A Field Guide to the Birds of North America, with ADAMS scrawled along the side. With one hand flipping the page of the text, while the other deftly maneuvers a Gray Catbird, the biologist identifies the bird’s age, examines and measures its wing, weighs it on a small digital scale, and affixes a small aluminum band to its leg. He quickly calls out the necessary data, which is written down by Chandra Goetsch, a postdoctoral researcher at BRI. The data collection and banding process lasts only minutes before Evan releases the catbird, who promptly disappears into the trees.

As an ecological modeler and the director of BRI’s Quantitative Wildlife Ecology Research Lab, Evan spends much of his time considering innovative ways to analyze large datasets such as the 2023 Maine Bird Atlas, or working with offshore energy wind developers along the Atlantic coast. When he can get into the field, he bands birds at BRI’s birding station in Falmouth, Maine, where he applies an in-depth knowledge of migratory songbirds to data collection.

Despite Evan’s current fascination and skill in identifying and working with a broad array of species, at an early age he displayed no predilection for birds. His grandparents, who enjoyed hiking and wildlife, often mailed him natural history guides, gifting him his first birding book—a golden guide—when he was seven years old. Evan laughs, “Let me tell you, I did not use it for much.” After a summer working at a particle accelerator in high school, and taking several science courses in college, it wasn’t until after Evan explored other fields that he found his way to birds. Evan describes being mystified as a child by his grandmother’s identification skills. “I remember my grandmother used to be identifying birds with me when we went on little walks together. She’d say, so that was a Western meadowlark. And I was like, how do you know these things?!” Now, Evan himself can draw up the names of countless birds at speed based on the brown streak on a chest (Song Sparrow), or a prominent mewing call (Yellow-bellied Sapsucker).

It was through a study abroad trip to Costa Rica that Evan had his first experience working with birds. He describes the opportunity, “Costa Rica is like the size of West Virginia, and it has more bird species than the entire United States. That’s what really got me.” Upon seeing beautifully vibrant Resplendent Quetzals, colorful Macaws, and large spectacular Violet Sabrewing Hummingbirds, Evan knew he wanted to pursue a career related to helping birds. During his doctoral studies, Evan worked part-time with BRI staff, but everything changed in 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill occurred in the Gulf of Mexico. He received a call from BRI’s science director asking him to aid in research efforts there. He moved to a full-time position with the Institute, researching various species, applying his skills to band migratory songbirds, and building the quantitative lab.

Evan dedicates most of his time to the Maine Bird Atlas, a long-term project to gain a better understanding of Maine’s breeding and wintering bird populations, information that will help conservationists, policy makers, and the birding industry of Maine. Evan is currently analyzing five-years’ worth of data collected by citizen scientists in the state of Maine. Working with a team of biologists across several government agencies and nonprofits, the group is carefully considering the best way to compile and share the information for easy access and informed decision making. Evan excitedly describes the opportunities to transform the information in ways to “maximize what we learn from it by taking datasets and turning them into analyses, or maps, or tools.” He adds, “I think there’s a lot of really interesting research questions that we get to answer now.”

Evan is a strong advocate for decreasing the gap between research and practice, seeking ways to transform science into actionable tools and resources that go directly into the hands of decision makers. For Evan, building relevant support tools involves understanding stakeholder needs and constantly asking the question: “Are we doing a good job of making a tool that people can actually use?” He continues to interact with a broad range of stakeholders to design research studies that will help answer pressing manager challenges. “There’s a lot of different ways you can build a research program that can inform decisions, but you have to be building it in collaboration with the decision makers, so that you know that you’re not just answering questions that no one has the ability to do anything about.”

Evan has found a home at BRI, whose mission of advancing environmental research and awareness aligns with his passion to inform bird conservation management and policy. Whether he is working to collect and analyze banding data collected at River Point Bird Observatory, abundance data of migratory and wintering birds for the Maine Bird Atlas, or patterns of wildlife behavior off the Atlantic coast in response to offshore wind energy development, Evan seeks to build channels of communication that improve conservation outcomes for wildlife.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

How to talk to people about climate change

By Alyssa Soucy, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Maine

Several times a year the topic of climate change makes its way to my family dinner table. After we finish our meal and clear the plates, the conversation moves away from the safety of discussing the weather or the latest sports game to climate change. Before we realize it, we are suddenly in a treacherous storm out at sea. We find ourselves in the middle of a dialogue steeped in politics, values, complexity, and uncertainty. Each one of us brings to the table our own experiences, beliefs, and worldviews, without so much as an oar to help us steer towards meaningful conversations that lead to attitude or behavior change.

Several times a year the topic of climate change makes its way to my family dinner table. After we finish our meal and clear the plates, the conversation moves away from the safety of discussing the weather or the latest sports game to climate change. Before we realize it, we are suddenly in a treacherous storm out at sea. We find ourselves in the middle of a dialogue steeped in politics, values, complexity, and uncertainty. Each one of us brings to the table our own experiences, beliefs, and worldviews, without so much as an oar to help us steer towards meaningful conversations that lead to attitude or behavior change.

As someone who studies how people think about environmental change, I see the dinner table as my laboratory. My family members become subjects for experimentation. While I attempt to move my family members’ beliefs and behaviors, I carefully watch how over time their attitudes have changed, and with it, their actions.

When the topic first arose years ago, I used what is commonly known as the information-deficit model of communication. This approach assumes that an individual’s lack of climate action is a result of them not having enough information. In other words, if we simply tell people the facts, those people will change. After spending much too long explaining greenhouse gases and carbon isotopes, my family was no more concerned about climate change, nor willing to change their behaviors.

Since the 1980s there has been an awakening in the field of science communication. Research consistently shows that giving people more information does not motivate action. It was therefore not surprising that the use of the information-deficit model on my family at the dinner table was uninspired. That is also one of the reasons why in a recent survey conducted by Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication, 72 percent of people in the U.S. perceive climate change as a threat, while only 58 percent support reducing fossil fuels, and 4 percent belong to an organized group for climate action.

Understanding that climate change is a global threat does not always mean that an individual perceives climate change as personally relevant or harmful, nor a priority in need of addressing. Talking about climate change in a way that fosters meaningful engagement is increasingly important to move individuals towards action.

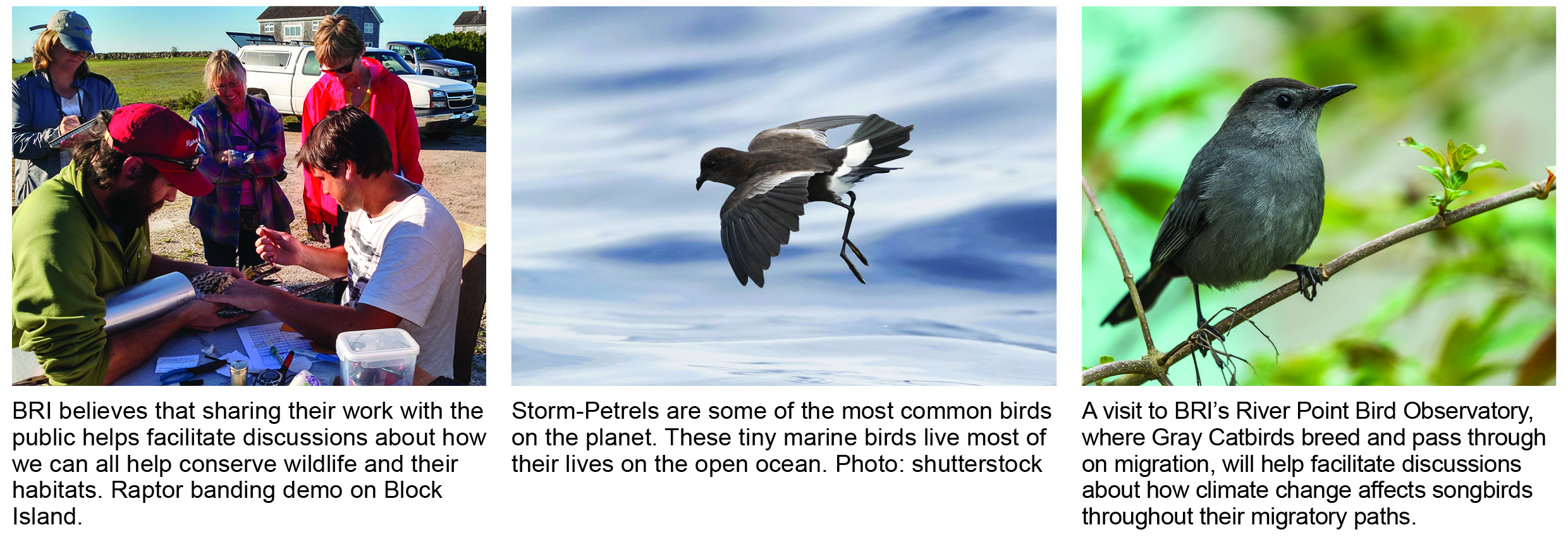

BRI’s scientists rely on many effective approaches, based on communication research, that lead to success when talking to people about climate change. These approaches account for individual values, experiences, and abilities, in addition to the many ways people interpret and act on information. BRI’s scientists are on the cutting edge of climate change research, exploring places and interacting with wildlife the rest of the world may never see. Iain Stenhouse, director of BRI’s Marine Bird Program, describes how few people even see the most common bird on the planet. “Some of these birds live over deep ocean for much of the year and then they breed in the Arctic. One of the most common species in the world is the Storm-Petrel. And probably 98 percent of humans have never even heard of it.” Therefore, making connections between individuals and the environment can be challenging as people may not always have the same experiences. However, Iain uses a powerful communication tool to connect people’s everyday experiences to birds. Employing a strategy known as synecdoche (where a part is made to represent the whole), Iain points to more common birds that people often see to get them thinking about larger ecosystems. “Birds are important indicators of the health of a major ecosystem that we all rely on for life,” says Iain. “And I’ve seen that resonate with people.”

Scientists and journalists have used a similar approach on a larger scale. Consider the animal that comes to mind when you think about global warming. For many (myself included), a polar bear floating on an ice sheet will likely forever be the image they associate with a changing climate.

Ed Jenkins, avian biologist who helps run BRI’s River Point Bird Observatory, uses visuals to communicate the importance of bird conservation. “I just thought posting loads of cool pictures on social media with everyone to see, with a little blurb about the conservation issue that species faces, would help support BRI’s goals and raise awareness of the work that we do.”

Visuals are a powerful communication device that can appeal to people’s emotions. Through engaging both in-person at the bird banding station as well as on social media, Ed shares a piece of the planet with the world that captivates audiences, while drawing attention to some negative impacts of climate change on the migratory birds. In this way, people feel connected to nature and more willing to act in ways that help the environment.

Tim Tear, director of the Center for Climate Change and Conservation, constantly considers climate change communication in relation to BRI’s work, emphasizing the importance of engaging with people’s personal experiences. He offers this example from his own life, “Growing up, we used to have to scrape bugs off our windshield all the time. And sometimes you would go to a gas station when you didn’t even need gas just to clean your window. That rarely ever happens at all now.” This experience provides a concrete example of environmental change.

While the impacts of climate change are all around us, the long-term nature of climate change makes perception difficult. Drawing on real, vivid examples, Tim lasers in on an important component of climate change communication: the use of personally relevant stories and experiences. By attuning individuals to the world around them, through all their senses, Tim believes that we can talk about climate change in a way that shapes attitudes and actions. He says, “Best to have things that people relate to in everyday life—that’s what makes it real.”

The art and science of climate change communication involves understanding the ways people interpret, process, and act on information. Since my unsuccessful attempt talking about climate change with my family using the information-deficit model, I have evolved in my approach. At one family dinner, I used message frames—powerful structures that people use to understand environmental change—to emphasize the personal economic costs of not mitigating climate change. “Continuing to use fossil fuels now will only result in larger costs to come,” I told them. Like Ed and Iain, I’ve shared images and information about wildlife they are interested in, describing the impacts of climate change on moose and loons in Maine. Like Tim, I’ve employed personal stories and narratives that bring the impacts of climate change close to home.

As people engage with science now more than ever, the people that communicate climate change play a critical role in society by shaping the direction, value, and meaning of climate science and policy. BRI continues to study and document long-term environmental change. This research, however, is supported by their communication work. Whether it’s conversing with people at the River Pont Observatory bird banding station, engaging audiences on social media, or creating captivating videos and imagery, talking to people in a way that motivates action is a necessary part of addressing climate change.

Tips for talking to people about climate change:

- Know your audience: Understanding individual worldviews, beliefs, and social and cultural norms is the first step in communication. If you know your audience is conservative, yet the views of their close friends and family are important to them, try talking about how climate action could benefit their relationships.

- Understand their barriers to climate action: If you hope to inspire change, there may be a financial, social, or other barrier to action. Do what you can to alleviate these obstacles.

- Use personal examples, including stories: When possible, connect climate change to something very real and important in a person’s life. You can draw on your own experiences to appeal to emotions as well as ask them about their own experiences with environmental change.

- Talk about climate change in a way that resonates with what a person cares most about: If people care deeply about wildlife, emphasize actions they can take to help wildlife. While those actions may also help to mitigate climate change, a person doesn’t necessarily need to believe in anthropogenic climate change to take action.

- Emphasize the short and long benefits of climate action: It can be easy to consider the short-term costs of mitigating climate change; for example, by installing solar panels. People often weigh the short-term costs over the long-term benefits. Consider the immediate short-term benefits when discussing mitigation actions and focus on these aspects in conversations.

- Bring impacts close to home: Use examples of climate change impacts that are both immediate and geographically close to an individual. This helps reduce what is called psychological distance, which can lead a person to care less about threats that are far away and in the future.

- Inspire hope and efficacy: Climate change can be scary and intimidating. Using scare tactics is not always an appropriate approach; rather, people need to feel hopeful that they can take steps to address climate change.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Informing policy on mercury and biological diversity

By Deborah McKew, BRI Communications Director

My four-year-old grandson is obsessed with finding mushrooms in our wooded yard. Last summer, he located at least 25 different species of mushrooms, different sizes, colors, textures and even personalities. Discovering so many mushrooms in our yard prompted me to do some research and wow, was there a lot to find. Currently, there are more than 10,000 known types of mushrooms. That may seem like a large number, but those who study these fungi (aka mycologists) suspect that this is only a fraction of what’s out there. “It’s amazing what we don’t know about mushrooms. It really is a frontier of knowledge,” says science journalist Michael Pollan in the documentary film Fantastic Fungi.

My four-year-old grandson is obsessed with finding mushrooms in our wooded yard. Last summer, he located at least 25 different species of mushrooms, different sizes, colors, textures and even personalities. Discovering so many mushrooms in our yard prompted me to do some research and wow, was there a lot to find. Currently, there are more than 10,000 known types of mushrooms. That may seem like a large number, but those who study these fungi (aka mycologists) suspect that this is only a fraction of what’s out there. “It’s amazing what we don’t know about mushrooms. It really is a frontier of knowledge,” says science journalist Michael Pollan in the documentary film Fantastic Fungi.

So why does the world need so many types of mushrooms, or spiders, or birds, or any other species? The answer is wrapped up in the term biological diversity. Every species on Earth plays an integral part in the health of our planet. When an organism becomes extinct, a wide web of other organisms suffers, and we all suffer in the long run. The study of mushrooms has helped scientists understand the intricate connectedness all species have to the earth and to each other.

As BRI marks its 25th anniversary this year, we reflect on the impacts our wildlife research has had in the big scheme of things. Some of our scientists have been studying the effects of mercury on wildlife and their habitats for more than three decades. But it has only been a little more than one decade that we started to see the results of our work filter up to the highest branches of government where policy is decided, and land-use management is carried out. Policy determines how we protect our environment and creates a platform to build awareness. Awareness leads to caring, and caring leads to action. Even small actions can lead to huge improvements in sustainability.

In the quest to conserve life on earth, many global environmental conventions have been initiated: Minamata Convention on Mercury; Convention on Biological Diversity; and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, to name a few.

Since 2011, when BRI executive director and chief scientist David Evers was invited to join the Scientific Committee for the United Nation’s Minamata Convention on Mercury, BRI has been delving deeper and deeper into the realm of policy. From participation on the scientific committee for this global treaty to remove and reduce mercury in the environment to an executing agent carrying out research around the world to help make that happen, BRI scientists have been at the forefront of informing high-level policy with a global reach.

As the threat of climate change continues to increase, a noticeable gap has emerged—the integration of these global conventions to achieve more than any single convention can on its own. BRI scientists are committed to helping make this integration happen. One major step towards such integration is the development of effective and efficient sharing of information to improve impact and policy effectiveness assessments. For example: the UNEP World Environment Situation Room maintains information on biodiversity and threats; BRI manages a global database on mercury data in biota; our scientists attend relevant Conventions; BRI produces scientific communications to aid in the political discourse.

To assess the effectiveness of the global conventions, and the countries that participate in these conventions, a necessary next step is to develop better ways to integrate information on biodiversity, threats to biodiversity, and efforts to reduce these threats. In response to the long-term need for evaluating the Convention’s effectiveness in reducing global environmental mercury loads, the Minamata Convention is working with Parties and other stakeholders through an Open-ended Scientific Group forum. These efforts by UNEP help to pave the way for improved information sharing and knowledge flow.

Biodiversity is critical to our survival. Teaching our children early to enjoy and respect the natural world can only help build the sustainable future we all want and need.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted in 1992, aims for conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of natural resources. The loss of biodiversity threatens our food supplies, opportunities for recreation and tourism, and sources of wood, medicines, and energy. It also interferes with essential ecological functions. The underlying causes of biodiversity loss are often complex and stem from many interrelated factors.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted in 1992, aims for conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of natural resources. The loss of biodiversity threatens our food supplies, opportunities for recreation and tourism, and sources of wood, medicines, and energy. It also interferes with essential ecological functions. The underlying causes of biodiversity loss are often complex and stem from many interrelated factors.

The CBD is launching its post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework that sets out an ambitious plan to implement broad-based action to bring about a transformation in society’s relationship with biodiversity and to ensure that, by 2050, the “shared vision of living in harmony with nature” is fulfilled. This BRI publication is available here.

Related Links:

Minamata Convention on Mercury