Loon Research in Massachusetts

BREAKING NEWS: First Successful Loon Nesting in Southern Massachusetts in a Century

BRI announces the successful results of its long-term loon translocation and restoration project Restore the Call: A male loon chick that was translocated in 2015 from the Adirondack Park Region of New York to the Assawompsett Pond Complex (APC) in southeastern Massachusetts returned in 2018 to the region from which it fledged, and now in 2020 has formed a territorial pair, nested, and successfully hatched a chick in Fall River, Massachusetts. The identification of this loon (through color bands) marks the first confirmed nesting pair in southern Massachusetts in more than a century.

Current Status

Population

In Massachusetts, a disjunct breeding population exists and is recovering in the state. Since 1985, this population has increased six-fold; by 2019, 40 territorial pairs were found on 22 lakes (Figure 1). While the population has increased, overall productivity—chicks surviving per territorial pair (CS/TP)—has slowed since the late 1990s.

Figure 1. Number of lakes and territories occupied by loons in Massachusetts.

Reproduction

In 15 of the last 22 years, the productivity rates in Massachusetts has been below sustainable levels (0.48 CS/TP; . The carrying capacity for Massachusetts is estimated to be about 300 pairs based on lake area, depth, and phosphorus concentrations. Therefore, larger breeding populations are feasible.

Seasonal Movements

Data from breeding loons banded in New England and New York, found recovered or re-observed live on wintering areas, ranged from Canada to Florida. Coastal Maine (36%) and Cape Cod, Massachusetts (36%) accounted for 72% of all wintering areas. This was followed by the mid-Atlantic (10%), southern New England (8%), Long Island, New York (6%), and coastal New Hampshire (4%). Continued banding is needed to better understand seasonal movements (since 1999, 107 loons have been banded).

Translocating

In 2015, in collaboration with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, BRI successfully moved seven chicks from New York’s Adirondack Park to a lake in the Assawompsett Pond Complex (APC) in southeastern Massachusetts.

In 2016, BRI translocated nine chicks to the APC (four from New York, five from Maine) with assistance from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife and Maine Audubon Society. Overall, 24 chicks were successfully translocated to Massachusetts.

As of spring 2020, nine adult loons returned to the lakes in Massachusetts to which they were translocated and captive-reared, and then from which they fledged. Their return marks a major milestone in the efforts to translocate Common Loons. See BRI publication: Loon Translocation: A Summary of Methods and Strategies for the Translocation of Common Loons

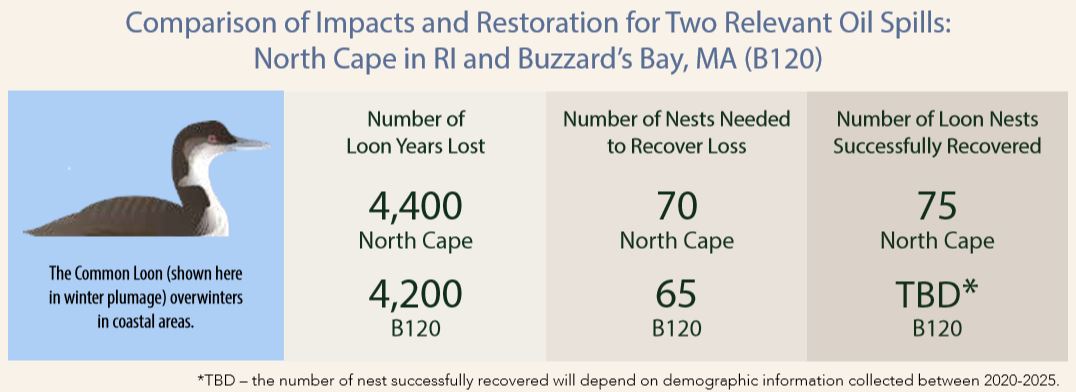

Marine Oil Spills

BRI has worked with collaborators to design and apply successful approaches to address conservation concerns to Massachusetts Common Loons from marine oil spills.

Bouchard Barge 120

On April 27, 2003, the Bouchard Barge 120 (B120) struck ground near Cape Cod Canal. Between 22,000 and 98,000 gallons of No. 6 fuel oil spilled into Buzzards Bay (U.S. Coast Guard 2003; Hall 2003).

This event occurred during migration of several bird species including the Common Loon. Approximately 200 dead or moribund loons were collected and a rapid field assessment was coordinated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) through the Loon Preservation Committee (LPC) and BRI to document the range and fate of dispersing individuals (Taylor et al. 2004).

Oil Fingerprinting

Dispersed loons with oiled plumage were identified in Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. A total of five loons were observed with oil in Maine and New Hampshire.

One of these loons was identified by its color bands and found on its traditional breeding territory in central New Hampshire. Another loon captured in New Hampshire was tested and found to have been contaminated by the B120 oil spill. This finding and other observations documented that the “footprint” of impact was greater than the immediate Buzzards Bay area. Pre- and post-spill data from monitored breeding loon populations in the Northeast helped identify further potential impacts to reproductive success.

Proven Restoration Strategies

In a precedent-setting 10-year restoration effort for the North Cape Oil Spill in Rhode Island, BRI worked with the USFWS to identify and purchase the best lake shoreline properties for mitigation. We then monitored the protected loon pairs on a weekly basis for two to six years. This long-term approach was successful in replacing and determining the loon years lost (adult loons that died from the spill as well as their lost future progeny). This strategy is being considered for the B120 spill.

Next Steps

Monitoring and banding efforts have allowed a detailed examination and understanding of the breeding loon population in Massachusetts—its demographics and natural history, as well as comparisons and benchmarking with neighboring state populations. Additional data is required to more fully determine the biological parameters used in NRDA’s calculations for loon-years gained through conservation actions resulting from the B120 oil spill. These knowledge gaps and recommendations to address them are presented in the following sections.

Adult/Juvenile Survivorship and Breeding Site Fidelity

Monitoring banded breeding loons in should continue during the breeding season. The annual count of returning loons and their associated reproductive outcomes will allow us to refine the demographic parameters required to model loon-years lost due to oil spills.

Translocated Loon Chick Return Rates and Dispersal

Documenting the successful fledging, returning, and breeding of translocated chicks is important for guiding restoration plans that utilize translocation as part of an effort to restore loon-years lost. Translocated chicks have fledged from both captive rearing and direct release approaches. We documented their successful return as adults in the summers of 2018-2019. Monitoring southeastern Massachusetts to resight returning loons translocated to that area will be important to document habitat use, movements, and breeding success.

Wintering Range and Winter Site Fidelity

Few wintering band resights and recoveries have occurred for Massachusetts loons due to the small number of banded loons and difficulty of obtaining these data points. In order to increase the understanding of this aspect of the population’s natural history, satellite telemetry tracking devices (PTT– Platform Transmitter Terminal) should be deployed on male Massachusetts loons.

Data obtained from this effort would provide insight into migration timing and pathways, wintering locations, and winter home range. Alternatively, the geolocator approach to investigating wintering loons requires recovery of the devices in subsequent breeding seasons, and the resulting location data lacks precision (100+ km spread in data points).